28 Days in BALME: Learning inclusive Architecture

Students exploring ideas of what makes a home—and a city.

Who are the authors of our urban spaces? How does the culture of private property shape the spatial design and aesthetic attributes of cities? In a traditional architecture education, these questions are often an epilogue, or even an aside, to a multi-year foundational training in form, aesthetics, and canon. But what if we flipped this order and began with these questions instead?

This past summer, Office of Collaborative Design (OFF-CODE), working with local nonprofit Digital Ready, had a unique opportunity to ask these essential questions to high school students taking an introductory workshop in architecture. Hosted at BSA Space, our intensive four-week workshop, It Takes a Village, conveyed fundamentals of design by drawing out student’s own conceptions of what makes a home and a city. Through their incredible efforts, students designed and built a 16’ city—they dubbed BALME (Black Asian Latino Minority Ethnic). The model culminated an extraordinary summer workshop introducing underrepresented young adults to careers in architecture, engineering, and construction.

Digital Ready, whose mission is to build tangible pathways to economic opportunities in Boston’s innovation economy, is one recent addition to apprentice design training programs in Boston. The barriers to design education and professional practice are severe: less than 2% of licensed architects identify as Black, and less than 3% identify as Latin. These highly exclusive filters of training and practice parallel the conspicuously exclusive processes of creating spaces and buildings in America, processes that have actively segregated and economically stratified our cities. Our studio confronted the exclusivity of the design professions by emphasizing how cities can be actively shaped by communities themselves: with reference to collective organizing around ownership, to non-binary and non-nuclear familial arrangements and use of space, and to how an aesthetic culture creates and shapes the built environment. In this way, we grounded design in relatable ways and encouraged our students to work collaboratively toward a shared goal, contributing their lived experience and their intuition as wellsprings of design creativity.

Throughout the summer, we encouraged the students to engage in collaboration, critical reading, and collective discussions to develop their understanding of the city and how urban and architectural space is divided and distributed in our society. We took outings to visit the Basquait and the Hip-Hop Generation exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts and facilitated group discussion with the progressive stack method, ensuring every student felt they could be heard. Students learned from daily series of professional speakers, some of whom were enormously influential role models, including Wandy Pascoal, Housing Innovation Design Fellow at the Mayor’s Housing Innovation Lab and the Boston Society for Architecture, and Loeb Fellow ’19 Jeana Dunlop, urbanist and strategic facilitator, whose works each seek and facilitate inclusive change in the built environment. “Honestly, Jeana Dunlop is one of the most amazing women I have ever met,” student Zaria said.

The studio was structured in three parts: researching, designing and building. In the first week, students conveyed personal narratives of family barbecues, street parties, outdoor festivals, and games as some of the memories that made their neighborhoods alive, animated, and distinctly their own. “The smell in the room is always changing, depending on what my grandparents are making,” Thao said. “Whenever I’m in these rooms, I feel comfort, since it’s always loud and full of life. It’s small, but we don’t need a lot of space to have fun. The advantage of being in a small space is it brings us closer together.”

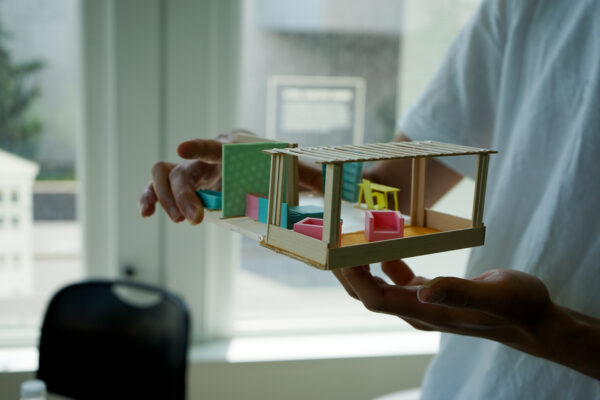

Then, in the second week, students were provided a common table on which to build their shared model of an ideal city. Arranging doll-house sized furniture, the students' personal narratives began filling the studio with dozens of tiny colorful rooms. Graduate student tutors instructed them in both analog and digital methods of model making and 3D printing, enabling the design ideas to come alive. This creation was framed through the reading of two texts: bell hooks’ [sic] Mapping Cultural Genealogy of Resistance and Delores Hayden’s What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design and Human Work. Each asks readers to conceive of the politics of spatial design or the merits of shared communal spaces. These critical readings—often assigned to graduate-level students—proved surprisingly resonant with our teenage students. Repeatedly students cited the shared communal spaces described by Hayden as an alternative they desired to privatized, exclusive amenities. For many, the “cultural genealogy of resistance” outlined by hookes [sic] inspired the students to name their city, BALME, as an aesthetic and spatial environment wholly their own.

We anticipated our students would be burned out from a pandemic year of virtual instruction and therefore our curriculum reduced abstraction and increased the sense of excitement, confidence, and accomplishment through hands-on making. At the outset, the students, ranging in ages from 14 to 23, had different levels of personal interest in design (including little or none). And yet they are in some ways initiative designers already. This age group is highly aware of appearance, aesthetics, and the “design” of one’s own personal identity (to say nothing of the intense consideration of personal expression on social media). They are also intimately aware of the ways their city nurtures or hinders their growth as adults.

The studio culminated with a hands-on creation of a pop-up installation, built in collaboration with YouthBuild Boston, a longstanding nonprofit that provides youth apprentice training to enter construction trades. Students were invited to work alongside other student carpenters their own age to learn basic skills in carpentry, site surveying, and teamwork. Working together for a few days, one of our students, who was reluctant at the outset of the summer, found himself inspired by the work and, at the end of the class, enrolled in the YouthBuild apprenticeship program. The pop-up features an immersive display of the students personal memories of home, the focus of the workshop that began as an individual journey and culminated in a collective creation. It’s a simple structure of wood poles, carefully cut and assembled into a framework supporting the student work adorning a flowing textile, set in the silhouette of a house.

During the final review, the room was packed with students and visiting professionals, all circling around the city model. In conversation, students spoke about their personal struggles with exclusion and feelings of pressure in an increasingly expensive city. “Boston is rebuilding itself,” Zenobia said, “but it’s in a way that I feel a lot of our voices are not heard, or are not contributing to the new building of Boston. Our model is very different from the way Boston is being built and changing.”

Citing hookes [sic] and Hayden, students revealed fundamental failings of their city. “My neighborhood only offers two-bedroom units,” Trish said. “If we wanted three-bedrooms, we would have to leave our neighborhood.” Students talked about ideas of a compassionate and inclusive city, with an abundance of public space and shared amenities, and above all affordable housing. Many students also shared the stress they’ve personally felt as their city changes. “I can’t go to a lot of places I used to enjoy,” Madisyn said. “Gentrification happened to me a couple of months ago: I had to move to a new place because we were kicked out by new tenants. This is a huge problem, especially during a pandemic.”

Ending on a more optimistic note, many students discussed how they felt emboldened by what the workshop had revealed to them about the issue of spatial injustice. “I never really thought about architecture until I came here,” Jason said. “We need more places we can go and find what we want to get out of life. That should be a change for the future of Boston.” For more than a few students, pathways into design, urban planning, construction, and activism seemed for the first time necessary and attainable.

As educators, we also took time to reflect on what we learned from this experience. A design education aiming to be more relevant and inclusive must reconceive the agenda of design. The immediate approach should be twofold: First, programs should reveal the array of professional opportunities in spatial design practices for students to explore—from architecture and trades to planning and activism—rather than elevating a single role. Second, we must demystify the mechanisms of spatial inequalities by equipping students with an awareness and understanding how form, economics, and policy coalesce into the urban realities they witness and endure. This way, design education can be grounded in reality and resonate with students, especially those who lack the privilege to enjoy design as a folly, but instead endure it as an enormous determinant of their health, wealth, and quality of life.