Hansy Better Barraza AIA

Co-founder and Principal, Studio Luz Architects

Professor of Architecture, Rhode Island School of Design

This interview is part of the BSA's Profile series on Hispanic and Latinx architects in the profession, conducted during Hispanic Heritage Month.

Hansy Better Barraza AIA is one of the 2021 Women in Design Award of Excellence winners and is a featured speaker at Intersections: Equity, Environment + the City, a hybrid symposium from November 6–13, 2021 centered around intersectional and participatory design processes.

When did you first become interested in architecture as a possible career?

I don't think my experience has been the kind of traditional path

where you go to open houses, or you have someone coming to your school

to talk about different career paths. That didn't necessarily happen. I

attended public school from elementary school all the way to high school

in New York State. I didn't really have access to that kind of

introduction to the field.

There was a life experience I had that made me curious about the field: growing up with my single mom. We were pretty transient, in terms of our living conditions as recent immigrants to this country from Colombia, South America. Through that kind of transient experience, although I never really lived in a home, I was inspired to. I longed to design a house one day for our family—for my mom and me. And so that longing for stability was something that pushed me into my interest in architecture.

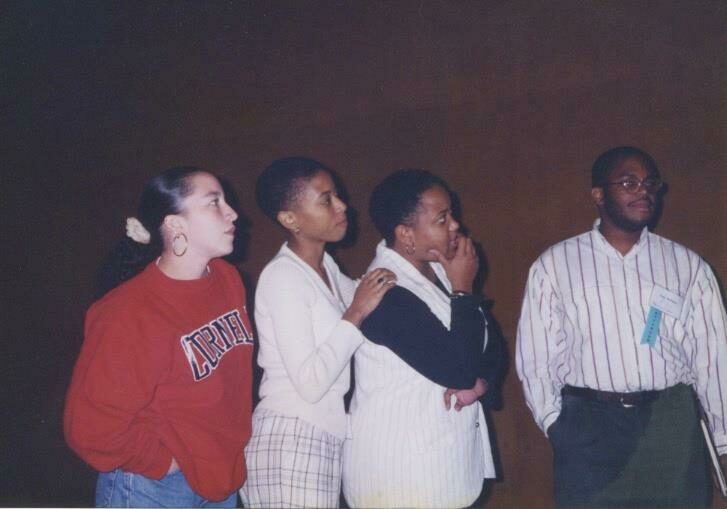

As a student at the White Plains High School, I had a formative architecture experience. I was part of a program of minority students committed to academic excellence that was being led by guidance counselors—all African-American women. This program brought students to visit Boston because of all the colleges and universities here and in Cambridge. With that kind of support from these mentors that were African-American, and from Latin leaders in my public school system, I was exposed to the idea that I could achieve my dreams and pursue a higher degree.

Those were the beginnings of my architectural interests. I also did a summer program at Cornell University, in my junior year of high school, which was a very important step. It got me out of the city and to a beautiful, bucolic landscape like Ithaca, where I was surrounded by so many interesting academic disciplines and students.

If you could give the you of 10 years ago advice, what would it be?

Since I have a business that I share with my partner, Anthony Piermarini, I wish I would have been a little bit more informed about the business operation and business development side of the field. Those things are just as important as design. That's the advice I would give anyone wanting to start their own business— that the design side is just as important as the financial and operational development side of an organization.

Who do you think is the most underappreciated architect and why?

I think that it's important to understand that there's been a lot of hidden figures in our design discipline. I taught courses about the erasure of Women and BIPOC designers in academia. I developed a collection of online directories of women architects who are queer or BIPOC in collaboration with my students through my Women in Architecture course offerings at Harvard GSD and RISD. Here are some resources for U.S. and global design institutions to eliminate excuses surrounding exclusionary practices in architectural discourse.

https://transformingthetimeline.com/

https://womeninarchitecture.cargo.site/

https://www.womenarchitecture.com/

What do you hope to contribute from your work?

Perhaps most of all, I hope to invest in my team members. It’s not just the principal, it's really the team. I also hope to contribute to developing a sense of ethics around the idea that as a designer and architect, you're in the field to make someone else’s life better. You're doing it because it's enlightening, or because it's making our environment more breathable.

I hope that our projects have a social impact, because currently our

work is in affordable housing and public art—university work that

interfaces with communities. I think going forward with a sense of care

and with the goal of making residents that are low-income achieve equal

access is crucial.

If you could collaborate with anyone in the profession, who would it be and why?

I'm currently collaborating with friends that graduated from Cornell University with whom I've kept in close contact. We have pulled together as a group since the tragic killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many more, due to police violence. We were a part of the NOMA (National Organization of Minority Architects) student chapter at Cornell. A couple of years later, we're now working together on projects and collectively looking to each other for not only support but also with the goal of doing bigger and better work around New England. Most recently, I collaborated with Nina Cooke John on a competition to design Providence's first permanent work of art. You can see our proposal here.

For future collaborations, I would like to begin to have positive joint ventures with other BIPOC designers. I would like to collaborate with DREAM Collaborative and with STUDIO ENÉE.

Which one of your current projects excites you the most?

In terms of my current projects, we're working a lot now with

affordable housing, and I think there's a lot of challenges in doing

this work because of the financial constraints. But I'm getting excited

about ensuring that, again, our ethics, our love for design, and love

for community comes through to make unique projects for the city of

Boston.

What does equity mean to you?

Equity means that our communities have equitable access to education and institutions. Equity means elevating Latinx sisters, immigrants, caregivers, entrepreneurs, activists, and those from low-income backgrounds. Equity means giving voice and power to those who have historically been oppressed by the systematic erasure of queer, Black, indigenous, and POC stories, lands, and cultures. Equity is reassembling oppressing systems into new, resilient networks of inclusivity.

What do you see as the largest barrier to equity in your profession?

Opportunities to do larger-scale projects, or getting on RFPs to do larger projects. Those are big barriers to retaining wealth in the long run.

What do you see as the largest barrier to a zero-waste building, city, and world?

Educating clients about environmental issues. I'm not getting clients

who are necessarily saying "I want to design a project that is zero

waste," and there should be more information out there to change that.

What is the greatest potential for architecture to shape a neighborhood community?

I would say that the greatest potential for shaping a community has to do with designing a project with an already-built ecosystem. For any neighborhood in which you're designing projects, you have to think about the walking distance to go to the doctor's, to go to the store, to go to school. I think that architecture and urbanism have a great potential to stabilize communities. Right now, the challenge is: how do we think about projects ecologically, through an ecosystems lens? If you ensure that there's a way for residents to go to a local doctor or school or daycare or place to eat, without using a car, you create the opportunity to build stability and to breathe.

What architectural buzzword would you kill?

Oh, I hate the word 'pivoting.' I never use that word. The concept seems to suggest ‘let's suspend and go the other way.’ I think it's just so temporary as a concept, versus a word that I love, which is 'rooted.' To be rooted is to really delve into, to really unearth and understand.

Where do you find inspiration?

I find inspiration from my really close friends that are doing varied work, from art, to design to political activism, to education. To give a shout out to the group of friends and creators in case you would like to follow their work, they are: Nina Cooke John, Emanuel Admassu, Andres Hernandez, Amanda Williams, Sekou Cooke, Marlon Forrester, Peter Robinson and Milton Curry.

What would you like to see change about Boston’s built environment?

I would like for there to be a vision about how we plan and how we build. I would like for Boston to be a little bit more avant garde. Because you know, we are diverse people. And so the architecture should express it. And we really need to think through how to achieve equity, and what I mean by that is we need to really find a way to support local businesses. And we need to really expand the numbers of Black and Latinx designers—I already said that. But I think what I really want is for Boston to mature and transform and change right now. I see that it’s still kind of stuck in its preservation.

Have you had a memorable experience while working on a BSA initiative that you would like to share?

I really enjoyed being on the board of directors for the Boston Society of Architects. I think it was a really great time and was important in my career development. I always look at the representation of the boards and the staff, and it's important that we stay inclusive and racially diverse.

If you could sum up your outlook on life in a bumper sticker, what would it say?

Be healthy and be happy. Isn't that what we all want, to be happy?