Jack Glassman AIA LEED AP

Historical Architect, U.S. DOI, National Park Service (Interior Region 1, Historical Architecture, Conservation and Engineering Center)

Degree(s):

B. Arch. Cornell University;

M.A. Historic Preservation Planning, Cornell University

Professional interests:

New design in historic context; interior and exterior streets; preservation technology

When did you first become interested in architecture as a possible career?

My father Herbert was a practicing architect (specializing in public schools) and a business owner with expertise in functional problem-solving; devoted to education, he also dedicated 60 years of time and energy to managing and growing the BAC, his beloved alma mater. I felt destined to carry the torch of architecture some day!

How do (or how did) you explain to your parents what you do for a living?

As the son of an inquisitive student of human behavior and the architect she married—no explanation necessary! When I was young, my dad repeated a cheeky question from an early mentor of his: “Architecture is a great hobby, but how do you intend to make a living?”

If you could give the you of 10 years ago advice, what would it be?

Take more career chances; don’t settle for the ‘comfort’ of the familiar.

Who or what deserves credit for your success?

I feel fortunate for the opportunity to blend a strong and well-regarded formal design education (B. Arch.) with a graduate degree in historic preservation planning, both from Cornell University. But all that had built upon an interest and enthusiasm for design and drawing nurtured in my high-school years by the BAC’s “Center Summer” Academy, led by Don Brown, and the MIT Educational Studies Program, where I was inspired by my architecture instructor, mentor and—for decades hence—dear friend of blessed memory, Francis “Chip” Piatti.

Who do you think is the most underappreciated architect and why?

Paul Rudolph, the underappreciated and perennially disrespected creative genius. With their attention to light and shadow, his incredible pen renderings of “great spaces” bring to mind the great Giovanni Battista Piranesi, a similarly unrewarded artist.

What is your favorite Boston-area building or structure?

I love the 1883 Hemenway Building at 10 Tremont Street, an extraordinary composition of brick and brownstone designed by Winslow & Wetherell (who also designed the Baker Chocolate mill complex in Lower Mills). Also, Alexander Parris’s ca. 1837 Ropewalk at Charlestown Navy Yard. Probably the only dressed granite Ropewalk on the planet, it has (finally) been rehabilitated as residential apartments.

Has your career taken you anywhere you didn’t expect?

As a child, I loved drawing cross-sections through an imaginary military base hidden beneath a Colorado mountain. What thrill, then, for the opportunity as a grown-up to repair and restore the 1833 Staple Bend Tunnel (Mineral Point, PA), the nation’s first railroad tunnel!

Which one of your current projects excites you the most?

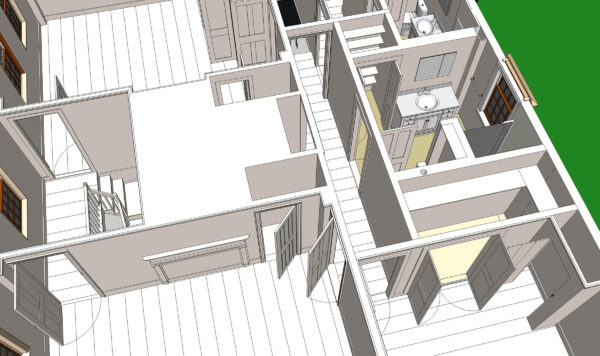

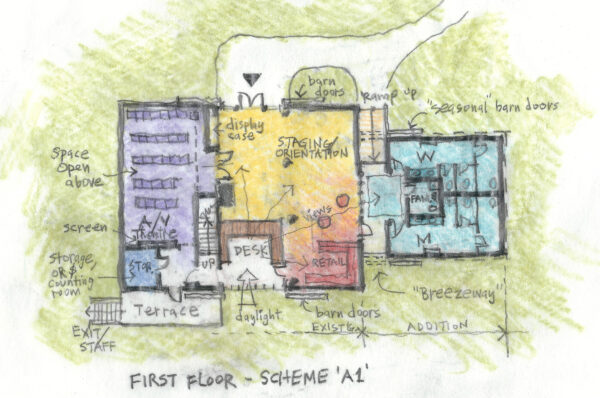

Our team recently completed a comprehensive repair and rehabilitation project for Minute Man National Historical Park, intended to spruce up the buildings and landscapes for the 250th anniversary of the April 19, 1775 Revolutionary War skirmishes. For this and other projects, I enjoy innovating ways to use SketchUp for the documentation and preservation of historic structures.

All photos: Jack Glassman AIA / National Park Service

What has been your most proud moment as an architect/designer?

Celebrating completion of restoration of the 1921 Plymouth Rock Portico, a rather small structure (and Rock!) experienced by millions of visitors annually. I was proud to bring together diverse professional disciplines, and to bridge technology and tradition, by crafting a project that uses solar power to protect the embedded steel frame from deterioration.

What do you hope to contribute from your work?

I love preserving and, where appropriate, updating historic structures, sites, and landscapes that make a positive difference

for users and visitors—offering delight and hinting at deeper stories.

This is my small contribution to education—almost a family legacy.

Have you won any award(s) from the BSA or another establishment? What elements from that project would you like to see shape the future of the profession?

The Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) Preservation Award for

the Plymouth Rock Portico restoration. The project was featured in the 2012 “Palaces for the

People, Guastavino and America’s Great Public Spaces” Exhibition at

Boston Public Library, as well as in

the national Preservation and Materials Performance magazines. With Gary Wolf Architects, my Orange Wheeler House rehabilitation/reuse project for the City of Lawrence YouthBuild program also won an MHC Preservation Award.

In general, I would like to see more recognition of a historic preservation sensibility that embraces the appropriate range of approaches and techniques as essential knowledge areas within design education and practice rather than “boutique” niches. Given the urgency for resilient and sustainable production and development, ongoing problem-solving attuned to conservation of natural and cultural resources is essential.

What does equity mean to you?

When inclusion is so ingrained in our public lives that those phrase modifiers, e.g. “woman architect" or “Black archeologist,” will finally disappear—while our appreciation and celebration of unity in diversity will continue to grow.

What do you see as the largest barrier to equity in your profession?

Pre-conceived ideas cast in concrete, as it were.

What are some changes that you have implemented in your firm (or for yourself) to address issues of equity in your profession?

I once found myself inadvertently “mansplaining” to a co-presenter

during a client presentation—or, at least it felt that way to me in

retrospect. Reflecting on that moment planted an important little

red-flag reminder in my head.

What is the most effective step you’ve taken in your work toward a more sustainable built environment?

As former AIA President Carl Elefante stated, the greenest building is the one that already exists. My work with existing and historic structures supports this precept.

What policy from another city sets an example you think Boston could successfully follow?

In 1970s Delft, Holland—long a bicyclist’s paradise—TU professor Jacques Volmuller promoted a concept of “mobility networks” to make car traffic, public transit, and cycling modes separate but interconnected. Boston and surrounding communities have made great strides in this regard, but could benefit further in selected locations by treating cars as visitors, rather than owners, of the roads.

What do you see as the largest barrier to a zero-waste building, city, and world?

Apathy! At the most cynical level, a collective feeling that small changes won’t make a difference.

What is the greatest potential for architecture to shape a neighborhood community?

By focusing on “the spaces in between” and the quality of the edges, and considering the existing figure-ground relationship of the neighborhood and resisting the push for isolated “signature” buildings except where really warranted.

How has design improved your daily life?

I am humbled every time I remember that most everything in the built environment was designed by someone; thought (and, probably, debate) went into the shape, color and feel of everyday objects, tools, interiors, and more.

Who do you most enjoy partnering with on a project?

I have loved working with structural engineers who (apparently effortlessly) exceed the “textbook” approach, and who are able to sketch out their innovative ideas and solutions.

What architectural buzzword would you kill?

“Gut-rehab”—kind of a macho ‘new-is-better’ reference to an outcome

that is not rehabilitation and certainly not ecologically sustainable.

Where do you find inspiration?

Complexity, pattern and so-called sacred geometry.

Regarding approaches to the adaptive use of buildings, I’m intrigued by the relationship between relative fit (think of a garment altered just for you by the tailor) and absolute fit (think of one-size-fits-all interchangeability).

What are you reading right now?

The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World, by Simon Winchester.

What was your least favorite college class?

Mechanical Systems. Our textbook had B&W photos of equipment that already looked vintage, and the subject was dry—but our professor was a good sport.

If you could redesign anything, what would it be?

First, my Boston City Hall Plaza makeover idea: carve (into the underground garage) a winding Utrecht-style two-level canal, lined with local cafes and retail, from the T stop down to North Washington Street! A new, human-scaled take on the original “Walk to the Sea” concept. Second, my neighborhood’s banal 1970s shopping/parking plaza, which treats the adjacent Main Street like a side alley.

What would you like to see change about Boston’s built environment?

Let’s do away with those fake window shutters and snap-in window muntins!

Have you had a memorable experience while working on a BSA initiative that you would like to share?

As Historic Resources Committee Chair from 2012-22, I sought out

featured speakers from within and outside the design community as a way

to prioritize the BSA’s outreach mission. Prior to that, I enjoyed

working with former Chair Henry Moss to produce a series of

(pre-digital!) poster boards highlighting architectural gems from each

Boston neighborhood.

If you could sum up your outlook on life in a bumper sticker, what would it say?

“Life… Minus Time Swerved.”