Kissing the nuclear family goodbye

Not quite a lifetime ago (in the 1950s), men wore hats, ladies wore girdles and schoolkids were periodically commanded to crouch under their desks, in the hope that those submissive postures would shield them from a nuclear blast.

Gas was cheap, cars were big, and zoning laws newly enacted to impose order on the headlong rush to turn farms into suburbs decreed that mom, dad, junior and sis should dwell in single-family homes forever and ever, amen.

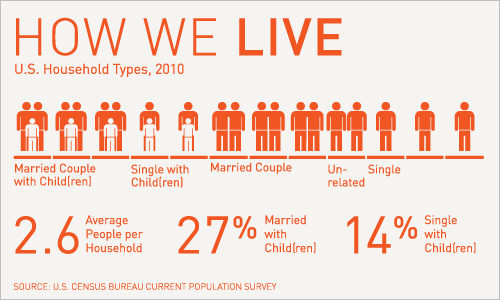

For most people, that America is a paling memory or, to Generations X and Y, like, ancient history. The nation now sports sizable populations of once-exotic hues and cultures; the United States leads the industrialized world in the percentage of households with children headed by a single parent (36%); those once-supple youth under the desks are now having a hard time getting up the stairs. And the economic engine long the envy of the world sits idle (or rusting) in the front yard.

Yet despite all those seismic shifts in who we are and how we live, the dead hand of single-family zoning retains its grip on the living by telling us where we may live, what shape our households must be, and how we may allocate the most precious asset we have—our homes.

It would be funny if it weren’t so hurtful.

Under zoning codes less rigid and exclusionary, a single mother (80% of single-parent households are headed by women) with unused space in her home might create an accessory dwelling unit, or ADU, which she might rent out to make ends meet or, perhaps, swap some portion of that rent to a student willing to help her with child care. Similarly, a boomer whose retirement savings were ravaged by the housing crash or the princely 0.1% presently being paid by a savings account, could develop a predictable income stream by renting a second unit. And many families faced with the ruinous costs of caring for an elderly parent could create an in-law unit to care for that parent at home—at roughly one-third the cost of a nursing home, according to a 2010 American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) study.

Moreover, considering that unpaid caregiving by family members is roughly $375 billion annually—almost four times the total spent by Medicaid (AARP, again)—federal and state governments should be doing everything in their power to encourage and support citizens shouldering that burden, including tax breaks and statewide revamps of zoning codes similar to California’s 2003 Assembly Bill 1866, which allows homeowners to create second units “by right.” Model municipal and state legislation already exists: All we lack is the political will to make it happen. That seems to be changing, though not quickly enough.

Consider, if you will, what the effects on healthcare costs and the national deficit might be if families could no longer afford that unpaid caregiving?

Then there is the NIMBY crowd, the defenders of nuclear-family zoning who grouse about government intrusion or invoke the hordes of riffraff (renters) who would destroy property values if in-law units were allowed. OK, let’s start by eliminating that government program that allows you to deduct the interest you pay on your mortgage from your federal taxes. Still there? And those fears about property values can be easily dispelled by a common-sense provision often adopted by those cities that have liberalized their zoning codes: Require homeowners with second units to live on the property. Landlords living on the premises will choose tenants as carefully and maintain their property as assiduously as any other homeowner.

If I’m being tough on those who prefer single-family zoning, it’s because the stakes are high and the hour is late. Many families in dire straits have compelling personal reasons to create second units, and they may do so whether they’re allowed to or not. At the very least, local governments should get out of the way as long as those homeowners exercise their property rights in a way that’s respectful of their neighbors and promotes the common good.

Which brings us to a final point: By creating modestly sized in-law units, such private citizens are increasing the stock of affordable housing at a time when cash-strapped local governments are unable to. They may also be contributing to the smart growth of their community by modestly increasing urban infill and, in effect, reducing the per-capita costs of city infrastructures.

Encouraging in-law units won’t cure all ills, nor will zoning reforms. But both acknowledge our present realities and steer us toward a more hopeful future.