Lawrence A. Chan FAIA Emeritus

Principal, Chan Urban Design

2010 BSA President

Degree(s):

B.A. (CCNY, Fine Arts), M.Arch (Berkeley) , M.Arch in Urban Design (Harvard)

Professional interests:

Architecture and Urban Design

Who or what deserves credit for your success?

Like most architects, I do not practice in a vacuum. I’ve been fortunate enough to have collaborated with, and received support from, numerous talented colleagues, architects and landscape architects, dedicated technical associates and staff, highly skilled engineers, interesting clients, cooperative builders, and inspiring teachers and mentors from the start of my career.

My partnership with Alex Krieger, with whom I co-founded Chan Krieger & Associates in 1984 (later Chan Krieger Sieniewicz in 2006), is probably my most significant collaborator. Our friendship dates back to 1975-77 when we were urban design classmates at Harvard Graduate School of Design. (In GSD parlance, we were ‘butt mates’ because our drafting boards were back-to-back throughout our studios together.) After we graduated and spent five years apart separately cutting our teeth at various offices, we established our practice and worked together until I left to practice solo in 2012, two years after our merger with NBBJ, while Alex stayed on.

Alex and I have had a similar approach to design while working closely for over 35 years. Our training in urban design expanded our perspective and articulation about architecture and how design fits, supports, and impacts the surrounding context. I think that helped us to communicate and develop rapport between ourselves and with our staff and many clients.

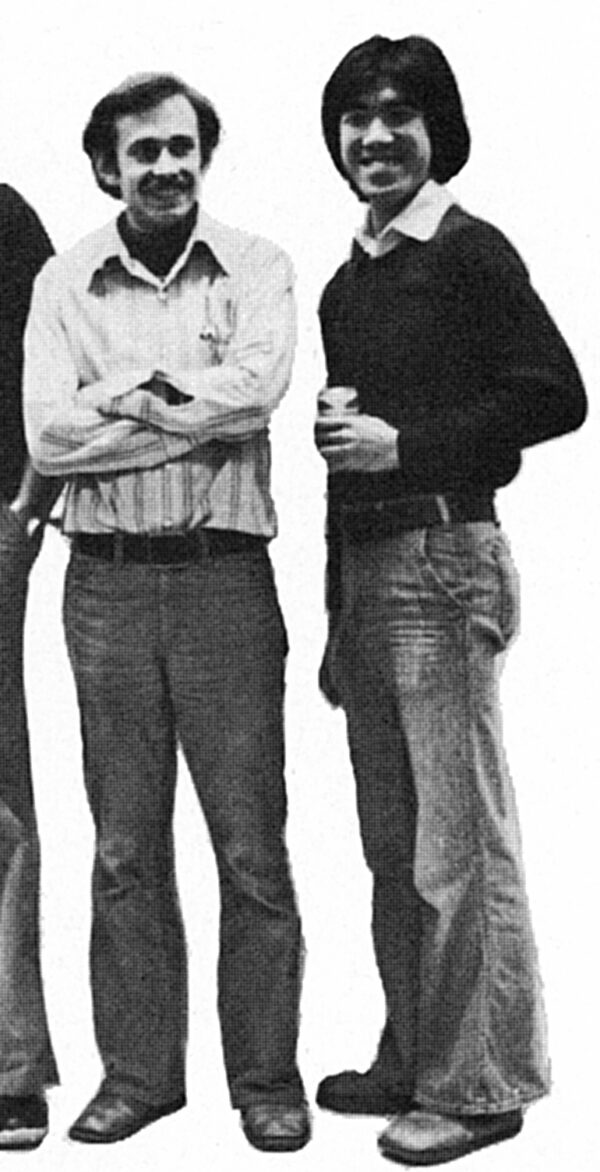

Alex Krieger & Larry Chan at Harvard, 1976. From 1976 Urban Design Program poster.

Larry Chan & Alex Krieger in Italy, 2018. Photo by Genevieve de Manio.

What is your favorite Boston-area building or structure?

My favorite structure is the 125 Lincoln Street Garage between Beach and Tufts Streets, across the street from Chinatown Gate. It was built in 1956 on a block that was truncated to create a wide corridor for the Central Artery Highway to pass between Chinatown and the Leather District. In 1973, architect Brian Healy FAIA renovated and redesigned the garage by adding new exterior cladding and an office level on the roof.

I admire the building, not so much for its former use or current state of deterioration, but for its potential to be sustainably repurposed as a signature structure that would reinforce the medium-scale, small business, mixed-use residential character of the Chinatown-Leather District neighborhood, for which the project sits immediate between.

I can envision the building transformed into an iconic civic edifice—such as a library and community center—with a diverse mix of shops and restaurants along the street level. A civic facility would be especially notable for the site when viewed through the lens of a classic Roman town center, where Surface Road is the north-south cardo, and Beach Street is the east-west decumanus, and the civic square is Chinatown Park situated at the intersection of the two cardinal streets. The civic square in the Roman exemplar is a sacred public space to which all adjacent buildings are subordinate in scale and use, except perhaps a market or a non-secular civic edifice which would be set off to a side—never at the very center of the intersection—which certainly does not apply to the high-rise laboratory tower that is currently being proposed as a replacement for the garage.

Which one of your current projects excites you the most?

The project that excites me the most is a 25-year master plan for a new city in Malaysia located 30 miles from Kuala Lumpur, the capital, and the international airport, that I completed in collaboration with Klopfer Martin Design Group, landscape architects; Utile, urban planners; and Buro Happold London, infrastructure engineers and planners. It was a career opportunity to plan an entire new city for two million people emphasizing transit-oriented development and sustainable initiatives, including the preservation and enhancement of the natural landscape by fifty percent.

The project, initiated by the prime minister, was quickly and enthusiastically approved at the state and federal levels, and received prominent press coverage. Unfortunately, major events after the plan’s completion have delayed the project, including changes in government, a financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Although I have received regular updates to be reengaged, the likelihood that the project remains intact becomes lower over time due to these factors and others.

What do you hope to contribute from your work?

Chan Krieger & Associates combined architecture and urban design as integrated disciplines in all of our work, which was not common practice when we founded our office in 1984. Urban design help us to be better architects by relating our work to the surrounding physical, community and environmental context, while architecture help us to be more effective planners by illustrating, demonstrating and explaining our urban design concepts.

Our approach is something I have consistently tried to instill while teaching studio or serving as a critic on student reviews. Just as architects need to incorporate technical and regulatory constraints into their work, I believe that they can benefit from incorporating urban design to understand broader issues that are not often articulated within a design program.

Urban design in our practice permeated through to many young architects who spent time in our office, and students with whom we had the privilege to teach. Two former employees come immediately to mind: one, a fresh architecture graduate from University of Cincinnati, and another from Princeton. Both had no exposure to urban design before working at Chan Krieger, but subsequently shifted their architectural focus towards urban design. Years later, both architects are in private practice emphasizing urban design, and the former is currently on the Harvard GSD faculty, with the latter on the Washington University College of Architecture faculty.

If you could collaborate with anyone in the profession, who would it be and why?

Coincidentally, I have just completed an international design competition submission in collaboration with two architecture firms: a small practice in Seoul, and a large practice in Cambridge. It was also a generational collaboration between firms founded in 1962, 1984 and 2003, and a twenty-plus-year age difference between me and the other principals on the team. In the end, I think we collectively felt very positive about the intense two-week effort, and pleased with the outcome. The experience confirms my feeling that any collaboration is possible with a good combination of project, personnel, skills, and chemistry between the people involved.

Collaborations—compounded by the time constraints of a design competition—can be exciting opportunities to discuss and share ideas that challenge us to sharpen our minds and pool our experiences, energies, and skills.

Have you won any award(s) from the BSA or another establishment? What elements from that project would you like to see shape the future of the profession?

One of Chan Krieger’s last projects, completed in 2010—just as we were merging with NBBJ—was the expansion and redesign of the Shanghai Bund waterfront, for which we won a two-stage international competition in 2007 in collaboration with Klopfer Martin Design Group, landscape architects. The project was made possible by the city relocating five lanes of the waterfront highway to an underground tunnel—similar to Boston’s Big Dig.

Central to our design concept is emphasizing connections between the city and the waterfront, especially where major downtown streets terminate at the Bund. Conceptually, the Bund serves as a one-mile long cardo with seven decumani, where each of the intersections has a uniquely designed civic square on the Bund. The key takeaway is for architects to take equal pleasure and value in designing urban space as much as designing buildings.

Architecture and urban space complement and co-exist with each other, metaphorically as yin-yang, positive-negative, push-pull, etc. The opportunity of designing an urban street corridor presents additional benefits and surprises that can extend beyond the immediate project site to influence the overall urbanity of a city and its adjoining neighborhoods. Incorporating urban design directly into architecture—rather than outsourcing it or treating it as optional—is something that I hope increasingly shapes the profession and its core teachings.

Tell us about your path to architecture and how it has impacted your career.

I had an atypical path to architecture. I initially majored in electrical engineering as an undergrad and transitioning to architecture courses, eventually majoring in fine arts for a B.A. degree. After attending graduate school for architecture, I completed a post-graduate degree in urban design at Harvard Graduate School of Design. There may be some anthropological explanation to my circuitous path towards architecture as a first-generation American, one of the first to graduate from college in my family, and a child of an illiterate single-mother who was a refugee-immigrant from China in 1948. This is one of several similar experiences that I share with Alex Krieger, who was born in Vilnius, Lithuania, and emigrated at age ten to the U.S. after WWII with his family after the Holocaust. That may have subliminally contributed to the rapport between us.

Another shared experience that Alex and I have is living our young adult years during the social and cultural evolution period in the U.S. during the 1960s and 70s. Urban design may have appealed to our approach to architecture because it presents a more contextual and global view of architecture that reflects our respective family histories and experiences growing up in America during the anti-Vietnam War and civil and human rights movements.

The Chinese population in America only started to grow significantly

after the 1943 abolition of the eighty-year-old Chinese Exclusion Act.

So, I grew up with a relative sense of isolation, feeling that I did not

belong and was not accepted as an American, despite being born in New

York City. I think urban design has given me a greater idea of how to

create a sense of community and connection.

What is the most effective step you’ve taken in your work toward a more sustainable built environment?

Many of the master plan recommendations that I developed for the new city in Malaysia—completed two years before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic—respond to the impact of climate change, and anticipate issues of zoonosis encounters where infected wildlife can pass coronaviruses onto humans.

The 25-year Malaysian master plan is for converting 43 square miles (slightly smaller than the city of Boston) of former palm oil plantation land into a new city with numerous initiatives to create a sustainable environment. These include preserving 50 percent of the land from development, protecting existing mature forest reserves, reforesting former plantation hillsides to restore lost or depleted forests, revitalizing riparian corridors to improve water distribution and control flooding, restoring agricultural land to promote local food sources and enhance food security, and creating a 15-mile-long ‘mountain-to-the-sea’ green corridor. The corridor will create a natural channel for environmental air quality and regional recreational opportunities between the permanent forest preserve and the Straits of Malacca.

Sustainable urban development recommendations include: creating a robust public streetcar network, reducing conventional parking requirements by 50%, incorporating tree-lined streets, restricting development on existing hills and steep terrain, and requiring all development areas to include mixed-use residential components.

Perhaps the most prescient recommendation is to create or reestablish

natural buffer zones—with agricultural or restored verdant land—between

development areas and forest preserves in order to diminish human

encounters with wild animals. The COVID-19 pandemic has made the world

more aware of the dangers of zoonosis that may be better prevented by

restoring natural habitats around wildlife preserves in order to

minimize interactions with, and transmission of, viral infections from

wildlife—especially coronavirus-infected bats—to humans and domestic

animals.

What is the greatest potential for architecture to shape a neighborhood community?

As an architect-urban designer, I instinctively look beyond the immediate project, whether the site is a building, campus, district, or region. It’s analogous to a photographer using a zoom lens to vary perspective in order to understand how the design might be influenced by its surroundings. I think this is especially significant when shaping a neighborhood community that encompasses a broad field of people, activities, and urbanity that may influence a project, its character, and its use.

For example, returning to 125 Lincoln Street Garage, I think the potential for the site should be considered beyond its economic value determined by a planning or land use map. The Garage site has a unique history of belonging to both Chinatown and the Leather District, neighborhoods that were dramatically severed by the Central Artery Highway. I think the site would have a greater community benefit through being integrated with the residential character of the two neighborhoods. A high-rise laboratory slab tower that would not only effectively segregate the two neighborhoods but also literally create an offensive and imposing wall between them.

An emphasis towards a civic-community-retail project would also help to provide some social justice to the area after decades of encroachment around Chinatown—from the Central Artery Highway on its eastern edge, Mass Pike and Tufts Medical Center on its southern edge, the Theater District (previously Combat Zone) and Emerson College on its western edge, and the Financial District on its northern edge. A mixed-use civic building would strengthen the bond between Chinatown and the Leather District rather than close the last perimeter and fence in and ghettoize Chinatown as a theme enclave for curious tourists.

Where do you find inspiration?

It can come from a variety of things and experiences, including taking a ten-mile walk around the Charles River on a beautiful day that would remind me of walking the Camino de Santiago three years ago from the Pyrenees to the Atlantic Ocean; seeing the eyes of a student light up from a design suggestion; watching sunrise and sunset; observing the curvature of the horizon and seeing the sky merge with the ocean; standing under the oculus inside the Pantheon; rediscovering the brass inlays in the brick walk on Winthrop Lane; or eating falafel and remembering a restaurant on the West Bank in Paris.

What are you reading right now?

I’ve been intermittently bouncing between three books. I am re-reading Thoreau’s Walden, inspired by living alone during the pandemic lockdown, which consequently prompted me to redesign, reconfigure and rebuild a portion of my loft. I’m also reading Sapiens, by Yuval Harari, for a deep dive into where we all came from; and a travel guide about Japan, for something to look forward to when travel becomes less chaotic and more encouraging—a bit of present, past, and future.

What would you like to see change about Boston’s built environment?

I would like to see a new innovative model for thinking about planning in Boston—perhaps in the spirit of the example I gave about 125 Lincoln Street Garage—that looks beyond conventional regulatory controls such as height, land use, and economic development opportunities to broader characteristics of city spaces and historical, cultural, social and intangible qualities.

For example, the current study area for the ongoing BPDA Downtown Plan demarcates an area defined by some of our most prominent streets, including Mass Pike, the Greenway, and Tremont Street. There is something counter-intuitive to a boundary that suggests that some things are left out, in this case the Leather District—which the City of Boston website links together with Chinatown as ‘Chinatown-Leather District,’ two complementary neighborhoods that are unequivocally linked and sharing a unique identity. Given this previously stated relationship, why isn’t the Leather District included in the Downtown Plan like Chinatown, its conjoined neighbor? Moreover, in the spirit of Jane Jacobs, it is inherently better to emphasize the street as a unifying element that binds together the character and strengthens the activities of both sides of a street, rather than designating it as a boundary that separates two adjoining areas, particularly residential neighborhoods.

Another change I would like to see is greater consideration and assignment of more civic, public and residential use of sites, such as parks, markets, and civic buildings, rather than allowing intrusive and disparate commercial projects that would only serve 9-to-5 weekday-only transient workers with no stake in the neighborhood. This might better serve people who live and thrive in the neighborhood.

Whom would you like the BSA to interview next?

Hubert Murray FAIA.

If you could sum up your outlook on life in a bumper sticker, what would it say?

When day comes we step out of the shade,

Aflame and unafraid.

The new dawn blooms as we free it.

For there is always light

If only we’re brave enough to see it,

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

Amanda Gorman, from The Hill We Climb