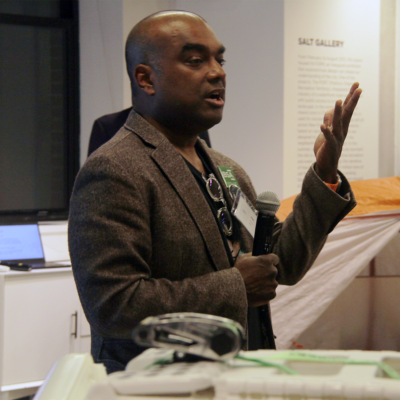

Q & A with Nigel Jacob: The BSA’s Innovation Work

What the BSA is undertaking, why, and what it aims to accomplish

What is your role at the BSA?

My new role at the BSA is Managing Director for Innovation, leading the innovation practice team. This team is focused on leveraging the skills of our members to target local issues—most notably the built environment’s impact on equity and climate. Our work is about experimentation: trying new approaches, learning, and iterating to improve the lives of those in neighborhoods and beyond.

What is happening in Greater Boston that demands the kind of innovation in the built environment that you have referenced?

There's a lot going on. We have a progressive woman mayor for the first time in Boston’s history—Michelle Wu—who has generated a lot of hopeful activity and excitement around the city. For the past decade or so, we've also had an amazing building boom. Yet, we are still struggling as a city. By all accounts, we are one of the most inequitable cities in the country, and we’re dealing with all sorts of systemic changes brought on by the climate catastrophe.

Given all these forces, now is an amazing moment to target these pernicious issues. It has often been said that Boston is resource rich and coordination poor. As an example, we have some of the greatest universities in the world within earshot. But we struggle to have a public education system where people of all backgrounds can expect to have their children educated. So there's a lot to be done to connect the resources to the most critical issues.

Innovation, in part, is about drawing a clearer circle around tensions, such as the dichotomy that Boston has experienced this building boom, but still has long-term poverty and inequitably dispersed resources across the city. This kind of tension is both a challenge and an opportunity to try new approaches.

What in your background prepared you to do this work?

When I was at the Mayor's Office, we started engaging differently with the community, serving the public in creative and non-traditional ways. And then Mayor Menino decided to create a group called the Mayor's Office of New Urban Mechanics that employed this experimental approach all the time. As we thought about new ways for government to interact with the community, it brought us into dialogue with all sorts of institutions involved in the built environment, including the BSA. The city and the BSA were able to do a variety of projects together over the years, looking at how we can take a more creative and thoughtful approach to understanding how the built environment affects people's lives.

I see my role at the BSA as somewhat similar to that I had at the city, working on the edges of the institution—in this case, the architect profession—with communities.

Given the challenges that you have mentioned, what is the BSA focusing on?

The innovation practice team is adapting the approaches of innovation—drawn from the design and tech sectors—to tackling climate and equity challenges in the built environment. We have actually been doing this kind of work for years, leveraging partnerships and collaborations to make life in cities better. The BSA involvement with the Boston Living with Water competition and more recently on the Future Decker project are great examples of this kind of collaborative, forward-thinking work.

The innovation practice that we’re developing is really acknowledging that we have been good at these kinds of initiatives over the years—and this is the foundation from which we are doing our new work. We are going to be leveraging our members and local institutions of all sorts to figure out how we invest in new approaches and methodologies to solve tough problems, learn from that, and let that inform what we do next. We are developing a more explicitly learning-driven methodology that taps into the knowledge and energy of builders of all kinds, architects, engineers, contractors, and developers to explore new territory. Central to this effort is including more voices in the process—voices that have historically not been at the table.

The innovation practice complements the BSA’s historical efforts to support the architecture profession through education, networking, and advocacy—all of which are ongoing. Our hope is that what we learn in the innovation practice will help inform this other arm of our mission—bringing new ideas and skills, including ways to collaborate with communities, to the table for consideration by architects and others in the building industry.

How is the BSA executing on this vision?

Before I got here, the BSA had gone through a process of looking deeply at where it wanted to go. Members got together, asked hard questions, and went through a process of design inquiry into the direction for the organization. We ended up realizing that we need a systemic approach to thinking about innovation and change at the BSA.

The process that the BSA settled on involves opening up a request for innovations of all flavors across the city—the first of which we issued last fall, asking the question: “How can we do architecture differently?” These Requests for Innovation—or RFIs, as we are calling them—yield different ideas and proposals, which we review for alignment with the BSA’s direction and goals. And, then we select projects to support and help develop as prototypes for making life better in Boston. We selected five finalists for the first RFI and are in the process of determining which of these we will take forward.

I think the dual goals of making life better in the community, and also learning from that and evolving the practice are really vital. We are trying to think about the RFI projects as a portfolio, which allows one to think critically about risk and reward, and then align these interwoven projects towards a goal, in this case solutions to equity and climate. We will be providing support to each project, in some cases funding, in others making connections, etc., and a BSA staff member will work directly with each project team.

We will be collecting data (both quantitative and qualitative) throughout each project and using this data to assess what was successful and what was not. There are several possible outcomes here: prototypes that panned out and can be scaled, prototypes that failed, or projects that we call “stale,” initiatives that seemed like they would work, but for whatever reason, we could not quite lift them off. I see this process as taking at least a year, but throughout we will be learning. By the end of this year, we should be able to share some of our initial learnings, as we set ourselves up for the next version of the RFI.

What results do you see that the innovation practice will yield?

We are trying to encourage the field to evolve. In order to build cities and communities that we need in the 21st century, we need to inspire change that allows for that. If we look to the future, I think “Mrs. Lopez”—someone living in one of the Boston’s neighborhoods—will experience changes that make her, her family’s, and her community’s life better. We will hopefully see a city that is addressing the needs of all, without certain populations, such as immigrants, being marginalized from access to services, transportation, etc.

In the short term, we will need to see what evolves from the prototypes we take on. The results will be borne out in the doing.

How can members of the AEC community get involved?

There are many ways to get involved, such as supporting a project, partnering with a community group, lending ideas to the innovation methodology we are developing and more. The short answer is that we welcome everyone to reach out to us at [email protected]. Our success depends on collaboration, so please come collaborate with us.