Remembering Donald L. Stull FAIA

Obituary courtesy of The Boston Globe.

With the two groundbreaking architectural firms he founded and led, Donald Stull designed Boston landmarks such as Roxbury Community College, the Ruggles MBTA station, the Harriet Tubman House in the South End, and Boston Police Headquarters.

Along the way he was celebrated for founding two firms that were owned and run by Black architects at a time when there were few such architects, let alone firms, in the country. Ultimately, Mr. Stull’s designs are more visible and enduring in Greater Boston than those of most architects from his era.

“Don was a talented architect, period, having nothing to do with race,” said his longtime business partner, M. David Lee, with whom Mr. Stull founded Stull and Lee Inc. in Boston. “He was a brilliant draftsman, a wonderful designer, and a thoughtful, philosophical practitioner. He enjoyed the respect of his peers.”

Mr. Stull died Nov. 28 in his Milton home, according to the obituary information his family prepared. He was 83.

In 1966, Mr. Stull founded Stull Associates, and Lee — while still in graduate school — began working for him three years later. After graduate school, Lee joined the firm full time, and the two later cofounded Stull and Lee.

“We were very much active in social change,” Mr. Stull told the Globe in 2010, during an interview in his Boston office. “We wanted people to have the opportunity to create their own destiny.”

They did so in part by creating one of Boston’s most diverse architecture firms, and perhaps one of the city’s most diverse businesses of any kind.

“It was like a mini United Nations,” Lee said. “We had people from Beijing to Boston who worked for us. We often brought women into the firm at high levels.”

Building such a firm was always one of Mr. Stull’s goals. At the time he founded Stull Associates in the mid-1960s, he was believed to be one of only a dozen Black architects in the country.

In a 1989 Globe interview, he said he had never attended any classes with another Black architect. Until he founded his own firm and began hiring a diverse staff, he had never worked with another Black architect.

When Lee arrived in Boston to attend the Harvard Graduate School of Design and arrived at Stull Associates seeking a summer job, Mr. Stull was happy to hire him.

“When I met David, I couldn’t believe it,” Mr. Stull said in 1989. “Here was another Black man who was studying to be an architect. I decided I wasn’t going to let this guy go.”

Together, they built Stull and Lee into one of the city’s most prominent firms, often against the odds. They faced racism — sometimes subtle, other times more obvious — in the development community.

“Being a Black firm has worked both ways,” Lee told the Globe in 1989. “We have had access to public sector projects driven by affirmative action goals. On the other hand, we have had to tell engineers: ‘Don’t just call us when you need minority representation on your project. Call us when you just want quality work.’ "

Their firm’s excellence was apparent in the $747 million Southwest Corridor project, for which Stull and Lee were lead architects and master planners. They designed the construction or renovation of nine Orange Line subway stations, along with a park that ran above them and stretched for miles.

The work earned them the Presidential Design Award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

The firm’s design of the memorable vaulted walkway at Ruggles Station, which connects Columbus Avenue and the Northeastern University campus, also was a point of pride.

“It is one of the most successful pieces of urban design from that era,” George Thrush, an architecture professor who was the founding director of Northeastern’s School of Architecture, told the Globe in 2010.

Globe architecture critic Jane Holtz Kay simply called Mr. Stull “one of the more talented and unrecognized architects.”

One of four siblings, Donald L. Stull was born on May 16, 1937, in Springfield, Ohio, according to biographical information on thehistorymakers.org website.

His mother, Ruth Callahan Branson, was a domestic worker who opened Ruth’s Place, a restaurant in Springfield, after World War II. His father, Robert Stull, had been raised by a white sharecropper in West Virginia before moving to Ohio, where he worked in a foundry.

While Mr. Stull was a boy, he began sketching and making carvings that were reminiscent of African masks, according to the website of The HistoryMakers, which collects oral histories. He became interested in architecture while working on construction sites with an uncle who was a bricklayer.

Mr. Stull attended the architecture program at Ohio State University and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1961. He then received a master’s from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

In 1970, he received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Ohio State. Boston Architectural College awarded Mr. Stull an honorary degree in 2011.

While at Harvard, he met the renowned architect Walter Gropius and after graduating initially worked at The Architects Collaborative, a Cambridge firm Gropius cofounded. Mr. Stull also worked at Samuel Glaser Associates in Boston before launching his own firm.

“Don came along at a pretty challenging time for Black architects,” Lee said. “Even today I think we only represent 4 percent of the profession. For him to succeed and have the audacity to start a firm in the mid-1960s is pretty amazing.”

Mr. Stull, who had taught at Harvard, developed a sure hand early on at designing affordable housing, Lee said.

“As a result of that,” Lee added, “he was able to attract clients and do some of the first afford housing around this area, even in towns like Stoughton and Amherst, in addition to doing projects in the Roxbury area.”

At the firm, Mr. Stull “had an infectious laugh,” Lee said. “He worked hard. He worked on the weekends. He was there, he was present, and was important.”

Mr. Stull’s longtime companion, Janet Kendrick, a former executive director of the Cambridge Community Center, died in 2008.

According to his family’s obituary information, Mr. Stull leaves two daughters, Cydney Garrido of Melbourne, Fla., and Gia of Allston; a son, Robert of Milton; a sister, Virginia of Dayton, Ohio; and two grandchildren.

Services are private.

Mr. Stull, a fellow of the American Institute of Architects, “was a charismatic guy. People liked to be around Don. He had good stories to tell. And he was a leader,” Lee said.

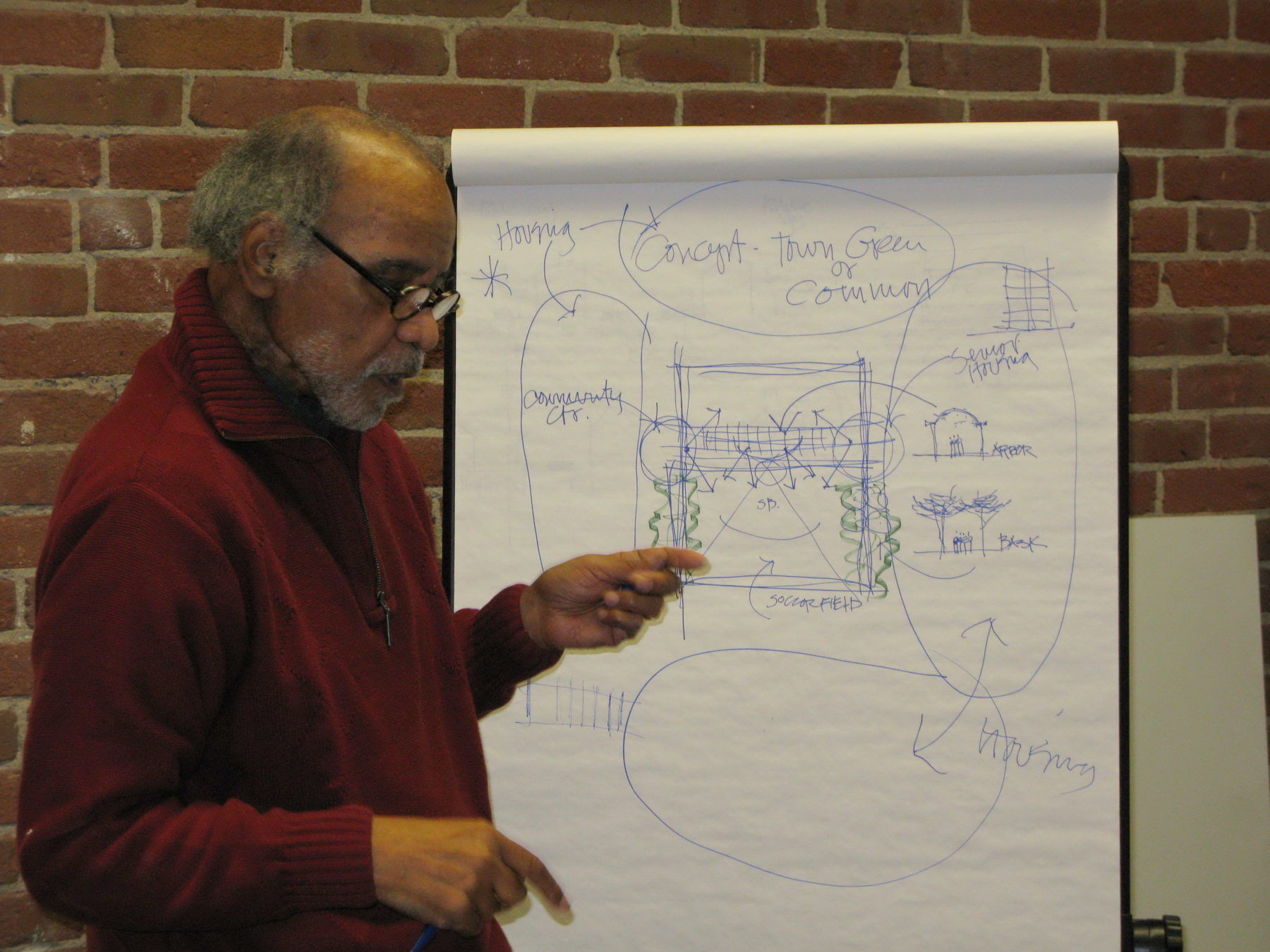

“There was a confidence about him that radiated. And people liked to listen to him,” Lee added. “He was so skillful in terms of his thinking and his ability to draw and frame design opportunities that I think people enjoyed being brought into that discussion.”

That ultimately drew young architects to the firm, including many who went on to form their own firms, carrying on Mr. Stull’s legacy of creating diversity in a largely white field.

“I’ve been told by many young Black architects who started firms that our firm had been a model for them,” Lee said, “and a lot of them looked first to Stull Associates, and then to Stull and Lee. Everybody wanted to work at Stull and Lee.”