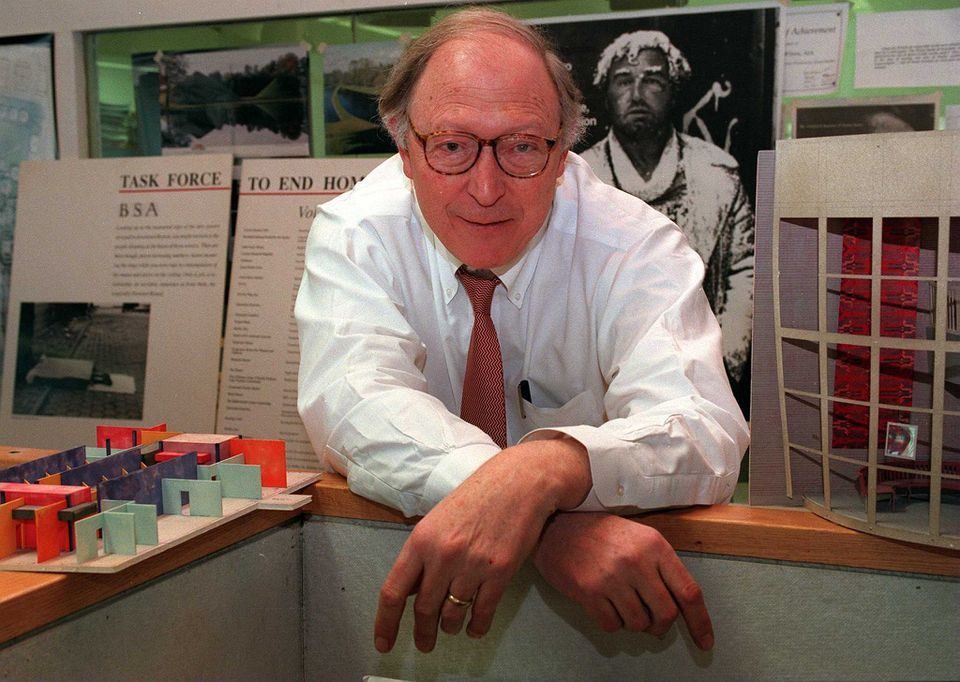

Remembering John L. Wilson FAIA

Source obituary courtesy of the Boston Globe.

As John L. Wilson cast his architect’s eye upward at Boston’s changing skyline in the mid-1980s, he was struck by the glaring contrast between the grandeur above and the poverty below.

“The architectural community was so excited that 26 different precious stones could be used in the lobby of an office building, yet there were people sleeping on the grates outside,” he told the Globe in 1996. “It was as if the money pumped into these buildings grew to represent the hope sucked out of the poorest urban neighborhoods.”

Mr. Wilson, who was 78 when he died in his Newton home last Tuesday of complications from dementia, was prompted by that troubling disparity to become an advocate for Greater Boston’s poorest and most neglected.

Drawing eventually on the pro bono talents of some 200 professionals in the field, he founded the Boston Society of Architects Task Force to End Homelessness in 1986.

“He absolutely served as a conscience for the profession,” said Elizabeth Padjen, a former president of the Boston Society of Architects and a former editor of ArchitectureBoston magazine. “Sometimes an organization or a board is lucky enough to have a member who serves as its social conscience, someone who will articulate its values and articulate a greater purpose. And John just did that.”

How to go about helping appeared challenging at first, however.

“I would ask, ‘What can an architect do?’ It’s an underpaid profession; we couldn’t afford to do a lot of free stuff all the time,” Mr. Wilson recalled during a pair of 1996 Globe interviews. “But we did some free front-end work. And I was able to attract some young architects and designers.”

Along with guiding the task force to work with more than 50 nonprofits, he both spoke out and wrote about why architects had a duty to help the homeless.

“Every place I walked in the city, there were people lying in the streets in tatters — in that era of total hedonism, of building all these projects with exotic materials,” he told the Globe. “I was outraged.”

For nearly 20 years, until merging into other design advocacy organizations, the task force helped improve and reshape buildings that house Greater Boston’s social service safety net.

According to “Designing for the Public Realm,” a publication that took stock of those efforts, the task force worked on more than 80 projects. The report also quoted extensively from Mr. Wilson’s writings.

“A society that allows some of its citizens to be without homes, sometimes literally living like animals, must recognize that it is structurally flawed, despite the superficial beauty of the monuments it erects,” he wrote.

As an architect and planner, Mr. Wilson helped create some of those attractive structures.

He spent his career as a principal at Payette Associates in Boston, except for a year teaching at the University of Toronto. His design work focused on health care buildings such as Leonard Morse Hospital in Natick, on which he collaborated with Tom Payette, the firm’s namesake.

Among Mr. Wilson’s other key buildings were a hospital in Athens, Ga., Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, and the Johns Hopkins Outpatient Center in Baltimore — “the first freestanding outpatient building in the United States,” Kevin Sullivan, Payette’s current president, said in an interview.

Mr. Wilson was a modernist who “loved to experiment with color, so his buildings were filled with color and natural light,” Sullivan added in an e-mail. “He brought humanity and high design to health care.”

John Leslie Wilson was born on April 3, 1941, in Spokane, Wash., and grew up in nearby Cheney, the son of Martha Leetsch and Victor Wilson.

After graduating from Cheney High School, Mr. Wilson went to Harvard College. “To get to Cambridge from my small town in eastern Washington in the fall of ’58, I took my first plane ride,” he wrote in the 50th anniversary report of his Harvard class. “There was a lot of landing and taking off — four stops in Montana alone.”

He received a bachelor’s degree from Harvard in 1962 and a master’s in architecture four years later from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

In 1964, he married Mari Ziegler, an attorney currently with the Morgan Lewis firm in Boston.

“He was wonderful,” she said. “He was a man of all parts.”

During his summers as a youth in eastern Washington, he worked on road crews. As a college undergraduate, he was a janitor at Harvard’s health services. While he was in graduate school, psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary tried to persuade him to set aside architecture and pursue psychology, Mari said.

Mr. Wilson was an avid reader whose packed floor-to-ceiling bookshelves in his Newton dining room were the envy of friends and colleagues.

Intellectually or physically, very little seemed beyond the reach of Mr. Wilson, who was 6-foot-4. At home, he did the plumbing. At the family’s vacation place on Cape Cod, he put a new roof on the barn.

“Wherever he went, he became immersed in where he was,” his wife said of his projects around the world. “He had the most incredible respect for the people he was working with.”

Such was the case in Boston when he founded the Task Force to End Homelessness.

“It was like the heavens had parted and he showed up to help us,” Dr. Jim O’Connell, president of Boston Health Care for the Homeless, said of Mr. Wilson’s work on the agency’s Barbara McInnis House respite facility in Boston.

“With very little money he made that place look like home,” O’Connell said. “John really knew how to turn an old tired building into a dignified place for homeless people.”

According to the task force’s history, its other projects included work with the Casa Nueva Vida shelter for homeless families in Boston; The Second Step organization in Newton, which assists those who have experienced domestic violence; and Bridge Over Troubled Waters in Boston, which works with runaways.

Mr. Wilson was a fellow of the American Institute of Architects. In 1996, the organization recognized his task force work by honoring him with its Whitney M. Young Jr. Award, named for a civil rights leader in the architecture field.

The institute praised Mr. Wilson for applying “design-thinking beyond the architect’s studio” as he “assembled multidisciplinary teams to solve specific problems, from a cash-strapped church building a soup kitchen to a bank opening a drop-in center for people experiencing homelessness.”

In addition to his wife, Mr. Wilson leaves their daughter, Victoria, and son, Sam, both of Newton, and his sister, Nancy Cashon of Spokane.

Plans for a service are incomplete at this time.

“For me, design certainly has moral or ethical overtones for our society,” Mr. Wilson told the Globe in 1996.

In his writings, he advocated for diversity in the workplace and diversity in the projects design firms choose to pursue.

And though Mr. Wilson was stoic as his health declined due to cancer diagnoses and other ailments, he was never silent about his advocacy for the poor.

“What is missing,” he once wrote, “is the outrage that this situation of poverty and homelessness can exist in the richest country in the history of the world.”