Walking the Camino de Santiago

A. Vernon Woodworth FAIA talks with Larry Chan FAIA about transformation along the path to the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

AVW: Larry, I understand that you completed a pilgrimage this past summer. Can you tell me about it?

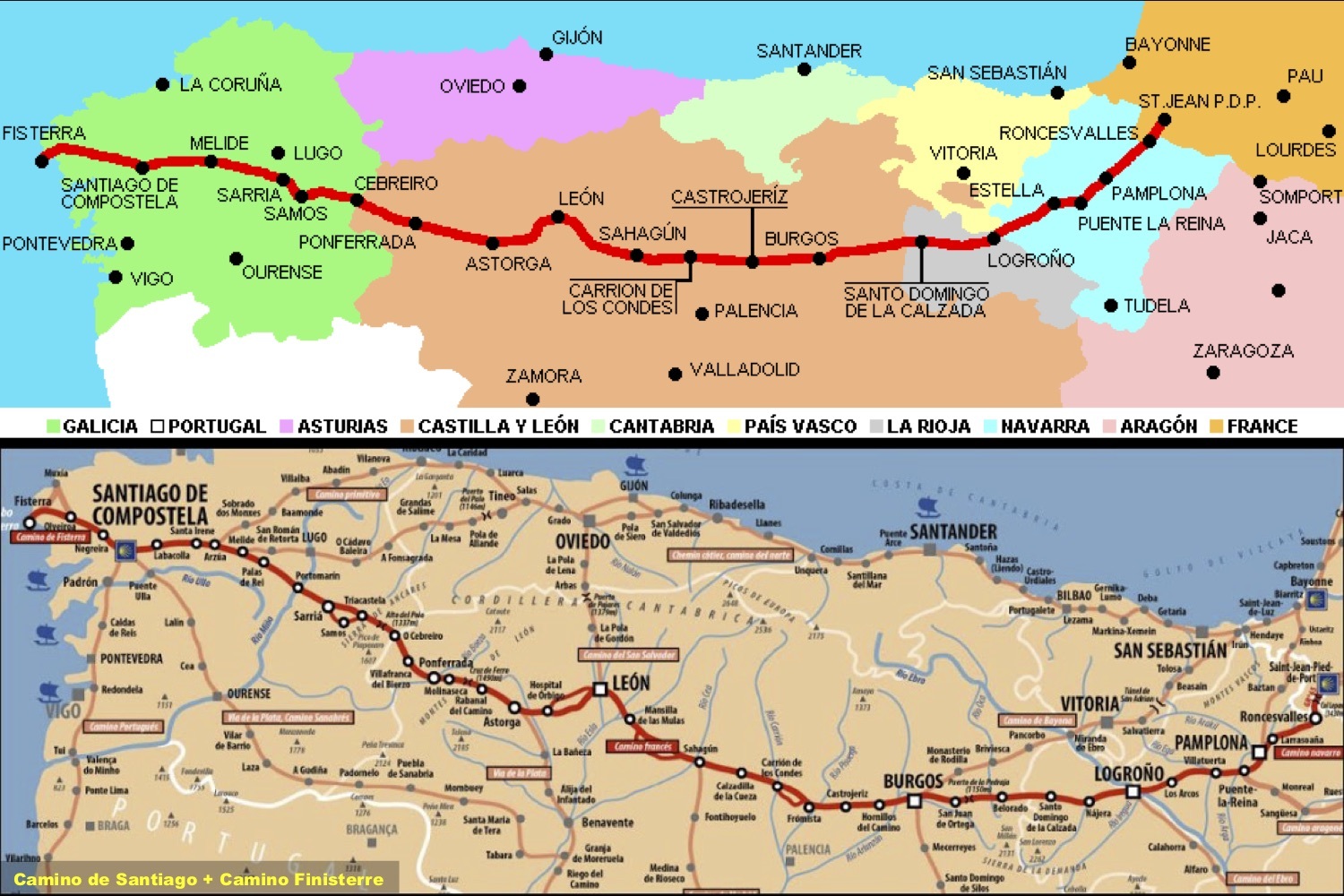

LC: Since the 9th century, the Camino de Santiago has been a religious pilgrimage from the French Pyrenees to the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, in northwestern Spain, where the remains of Saint James the Great, an apostle of Jesus Christ, are said to be buried. The path has since evolved into a network of paths with numerous starting points throughout the Iberian Peninsula and beyond. The original path, The French Way or Camino Francés, and the routes along Northern Spain are courses that have since been listed in the World Heritage List by UNESCO.

In modern times, hundreds of thousands (over 300,000 in 2017) have followed the routes for a variety of personal reasons, including: religious retreat, spiritual growth, travel, or sport. Most travel by foot, some by bicycle, and a few by horseback or donkey. I walked the original path, Camino Francés, from Saint-Jean-Pied-du-Port in France, to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain, and added the path’s most common extension, the Camino Finisterre, from Santiago to Cape Finisterre on the Atlantic coast of Spain known during the Roman era as the end of the world until Christopher Columbus reached the Americas.

The total official distance is listed as 550 miles (890 kilometers), as measured on a map. However, when including the inclines of numerous hills and mountains, off-trail wanderings, and rest day explorations, the total distance that I completed was over 700 miles or more than 1,450,000 steps according to the pedometer app on my smartphone.

AVW: I saw a sign during the Pan-Mass Challenge bike ride that said “If it doesn’t challenge you, it won't change you.” Thoughts?

LC: I did not set out to walk the Camino de Santiago as a personal challenge but as a memorial dedicated to Joyce Chong, a friend who I had known and loved for 53 years, and who died in the fall of 2018. I was abroad at the time and only learned third-hand that she had passed away almost a week earlier. Since teenagers, no matter how far apart our individual lives took us, through different colleges and careers, and separate relationships and marriages to others, we had always maintained a friendship enhanced by freely talking and confiding in each other. So, it was a sudden and shocking event to learn belatedly of Joyce’s death, and not having an opportunity for a final conversation with her or to say goodbye. I sought out the Camino as a place and time to grieve and to commune with her spirit. As I discovered throughout my walk, there have been many other pilgrims who have walked the Camino for a similar reason—bereavement—as evidenced by left-behind photos, stones, and small commemorative monuments dedicated to friends or relatives.

Although I completed significant research about the Camino, I did not fully appreciate that it would be a challenge despite the fact that I had never previously traversed through unknown forests or over mountains, traveled solo for two months, trekked distances in excess of 15 miles in a day, or walked even longer distances (up to 26 miles) on as many as 6 sequential days. I had thought that my previous 7 weeks of training in Boston consisting of walking 12- to 15-miles every other day would properly condition me for the trip. I learned that I was seriously mistaken after the very first day. Walking at sea level with no backpack was relatively insignificant compared to carrying a 25-pound backpack while multiple times per day ascending and descending muddy or rocky trails that occasionally reached as high as 5000 feet.

On one hand, one can conclude that I successfully overcame multiple challenges that often occurred in groups or simultaneously, including: pouring rain, progress-hindering wind, near-freezing temperatures, shadeless tropical temperatures, ankle-deep mud, mountain-goat inclines, slippery or unstable stone surfaces, and a multitude of physical aches and injuries over every part of my 70-year-old-body. On the other hand, since my mind and heart were focused on completing a personal memorial service, I accepted the challenges as mere inconveniences or fundamental prerequisites necessary to complete my intended mission. As a consequence, I was and am not consciously aware if there has been any impactful change that can be concretely articulated, described, or measured. Some obvious changes, such as losing 20 pounds, improving my aerobics, and getting stronger leg muscles are relatively irrelevant as compared to an intangible expansion of my sensory experiences through sight, hearing, smell, skin, breath, feelings, and emotions.

- Change has a considerable psychological impact on the human mind. To the fearful it is threatening because it means that things may get worse. To the hopeful it is encouraging because things may get better. To the confident it is inspiring because the challenge exists to make things better.

—King Whitney, Jr. - It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.

—Charles Darwin

I chose the Camino de Santiago because it has a mature network of support—unlike wilderness trails, such as the Appalachian Trail—including ready shelter, sustenance, and emergency and transportation services that a novice hiker of advanced age like me needs in order to safely complete the journey. Tiny hamlets, modest villages, towns, or small cities can be found every two- to five-miles. Moreover, the popularity of the Camino as a pilgrimage trail means that one is never alone for any extended length of time. So, regardless of any challenge, such as harsh environmental conditions or physical setbacks, all that was required of me was to intrepidly soldier forward trekking an average of 16 miles each day in order to reach the next destination on my planned itinerary.

For sure, there were long stretches when I felt overwhelmed by difficult conditions, but these were counterbalanced by priceless moments of wonder and surprise, such as: seeing the sunrise after climbing to the top of a mountain; inhaling and tasting the fragrant air of a new morning; reflecting on the vast natural landscape of Mother Earth as far as the eye can see in every direction; succumbing to the blue magnificence of the boundless sky wrapped over me; listening to the stillness of the forest or the rush of a river; absorbing valley winds coursing through and cleansing my body and mind; feeling the millennium of spirits embracing and helping me to release my grief while sitting alone in an ancient church; and sensing instant simpatico when meeting strangers from distant lands, sharing personal stories, and developing lasting friendships.

- If you are not spending all of your waking life in discontent, worry, anxiety, depression, despair, or consumed by other negative states; if you are able to enjoy simple things like listening to the sound of the rain or the wind; if you can see the beauty of clouds moving across the sky or be alone at times without feeling lonely or needing the metal stimulus of entertainment; if you find yourself treating a complete stranger with heartfelt kindness without wanting anything from him or her . . . it means that a space has opened up, no matter how briefly, in the otherwise incessant stream of thinking that is the human mind. When this happens, there is a sense of well-being, of alive peace, even though it may be subtle. The intensity will vary from a perhaps barely noticeable background sense of contentment to what the ancient sages of India called ananda—the bliss of Being.

—Eckhart Tolle, A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose

AVW: I think of pilgrimages as a form of ritual, and movement/transition as central to ritual. Van Gennep defined rites of passage as "rites which accompany every change of place, state, social position and age." He has shown that all rites of passage are marked by three phases: separation, margin ( or limen, signifying "threshold" in Latin), and aggregation. The first phase (of separation) comprises symbolic behavior signifying the detachment of the individual or group from an earlier fixed point in the social structure. During the intervening liminal period, the characteristics of the ritual subject are ambiguous; she passes through a cultural realm that has none or few of the attributes of the past or coming state. In the third phase (reaggregation or reincorporation), the passage is consummated. The ritual subject is in a relatively stable state once more and by virtue of this, has rights and obligations vis-à-vis others of a clearly defined and structural type. Do you feel that you have achieved a newly stable state as a result of your experience?

LC: Since I was walking the Camino de Santiago as a personal memorial to a dear friend, I do not believe that my journey was a ritual in the conventional sense that Webster defines as “a religious or solemn ceremony consisting of a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order” or “a series of actions or type of behavior regularly and invariably followed by someone,” nor was it a rite of passage marking an important stage in my life since I did not intend to walk the Camino for myself. Nevertheless, I would agree with Van Gennep that I did experience the three relative phases that he suggests as separation, transition, and aggregation.

Separation

The various environments along the Camino—including thick forests, steep mountains, and open plains—provided the desirable venues that I sought to spend time alone to harness my thoughts and memories of Joyce, and to commune with her spirit. While solitude is always an option on the Camino de Santiago, it is also reputed to offer opportunities to meet other pilgrims from around the world, both on the trail and while staying overnight in the network of albergues (group lodgings) that are widely distributed throughout the Camino system. My desire for solitude was implemented by electing to walk alone, booking private lodging in small hostels, pensiones, and rural hotels, and foregoing the camaraderie associated with the albergues. So, my proactive detachment was not only away from the familiar setting of Boston but also from the social milieu of the albergues. Nevertheless, due to the popularity of the Camino, mutual encounters are ubiquitous, however brief, while passing one another on the trail or during rest and meal stops. In my case, I met people from Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Germany, Guatemala, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan (although China would say this is part of China), UK, Uruguay, and USA. So, unless one is obsessed with complete isolation, separation is never complete.

Transition

Since my only previous travel in an Hispanic country was Barcelona, I felt relatively uncomfortable in my new environment, especially since I was unfamiliar with Spain and did not speak Spanish. However, the cultural transition was made easier by the predominant friendliness of the natives—many having some knowledge of English—and the plethora of other international travelers who spoke English. The common endeavor shared with other pilgrims provided easy and ready camaraderie that relaxed any anxiety or ambiguity of being in a strange place or situation. As a result, I had a handful of encounters with other pilgrims that encouraged me to temporarily suspend my self-imposed seclusion and enjoy the company of others by walking together, engage in extended conversations, and socialize during rest stops. Some of these encounters have resulted in ongoing friendships and correspondence with fellow pilgrims from Sacramento USA, South Korea, the Netherlands, and Germany, with occasional assistance from Google Translate. As a closet introvert, I have discovered that the ease of conversation and friendship is a significant new territory for me, affirming Van Gennep’s observation of personal transformation.

Aggregation

I am not sure that my Camino experience has manifested into a condition where I have entered into a new state—whether stable or dynamic—that is “clearly defined and structured” that contrasts with my previous state, or includes any “rights and obligations to others.” For me, my journey resulted in two distinct experiences: (1) an extraordinary walk through forests, mountains, and plains; and (2) a more-freely opening of myself to engage others towards new friendships. As a lifelong urbanist, born and raised in New York City and having spent the majority of my life living in major cities across the U.S., my two-month walk through the Spanish countryside has certainly given me a greater perspective and appreciation of Nature, and reaffirms my respect for landscape that has been an integral part of 40+ years of practice as an architect and urban designer. So, rather than a new state of mind, I would characterize this half of my experience as an enhanced state.

The second half of my experience of relaxing my innate introversion is indeed a relatively novel and untested state for me, especially in crossing over to new cultures, languages, and geography, that suggests an inherently unstable state—contrary to Ven Gennep’s statement—especially when compared to my previous state prior to walking the Camino. However, this is not necessarily a negative condition, particularly when applying thoughts about responding to change according to King Whitney, Jr. and Charles Darwin. Eventually a stable state may be achieved as my new relationships mature, or perhaps wilt away through passive neglect or inactivity.

AVW: Humans orient themselves in terms of location, time and identity. Our need for homeostasis motivates us to seek to stabilize these variables. Ritual provides a contained means by which to alter our relationship to these points of reference. With this in mind, what does it mean to be a pilgrim?

pilgrim |ˈpilgrəm| noun

- a person who journeys to a sacred place for religious reasons.

- a person who travels on long journeys.

LC: It is inconclusive to generalize on what motivates pilgrims who walk the Camino de Santiago or how they orient themselves. While the physical challenge of walking 500 to 700 miles would make it difficult for people to find homeostasis while in the wilderness and open fields, the network of rest stops and presence of other pilgrims offer numerous and various opportunities to stabilize one’s sense of location, time, and identity. So, there is an ebb and flow to one’s sense of homeostasis and one’s individual perceived points of reference before, during, and after completing the Camino.

In most cases, pilgrims walk the Camino de Santiago as a personal journey, affirmed by several who had shared their individual purposes with me, including: to decide what to do after completing college; to seek some wisdom on what new purpose to pursue, whether in early career, mid-life, or after retirement; to determine how best to terminate a one-sided or unrewarding relationship; to seek temporary reprieve from a repressive ethnic or social culture; to undergo an adventure of walking across the Spanish countryside; to challenge oneself by attempting an arduous journey; to enhance a friendship with another or others through a shared escapade or feat; to check off an item from a personal bucket list; to learn about a new culture and experience new cuisines; to meet others and expand one’s social universe; to experience the Camino as described and lauded in numerous sources; or to combine any or all of the above.

For me, my original purpose in walking the Camino was an offering and memorial to a dear friend rather than to proactively discover or better myself. So, I did not enter the pilgrimage as a pilgrim as more commonly associated with the Camino de Santiago. The feelings of introspection and adventure that emerged during my journey were unplanned, unexpected, and surprising developments that added to and recalibrated the walk from offering a tribute to receiving a benefit. As a consequence, I felt a spiritual aura cast upon my journey that may be attributed to the intangible essence that emanated from the path’s history, coupled with the spirits of hundreds of thousands of souls that had previously tread the Camino. In the end I derived tremendous satisfaction for successfully completing the course, and experiencing an unparalleled accomplishment of a lifetime. The ethos surrounding the Camino experience suggests that my daily communions with Joyce were successful, and the reward that I enjoyed, and continue to enjoy, is her parting gift to me in return for my humble endeavor.

To define what it means to be a pilgrim, one needs to first establish a moment in time. The start of the journey provides a different perspective than the journey’s completion. At the beginning, the pilgrim is an explorer, adventurer, or believer driven by a sense of purpose, endeavor, or mission. After completing the journey, the pilgrim remains a pilgrim, not so much as physically treading a trail, but following one’s path through life in a new state of mind with—paraphrasing Eckhart Tolle—“….a sense of well-being, of alive peace, even though it may be subtle….(t)he intensity…vary(ing) from a perhaps barely noticeable background sense of contentment to what the ancient sages of India called ananda—the bliss of Being.”

AVW: What is it like for you now to be back in a 21st Century city?

LC: The question implies that urban Boston is of the 21st century and modern, while rural Spain is of a bygone era, and thus anachronistic, and that my experience in each place has been or was sustained in a different existential state. While there are obvious differences in physical and natural attributes, population and density, culture and society, a more topical question would be: “What have I extracted from my two-month sojourn in Spain upon returning back home in Boston?”

Boston is a 390-year-old, major American metropolis with robust international connections in education, transportation, medicine, finance, and technology, while the 9th-century Spanish region through which I passed along the Camino Francés is more tangibly associated with agriculture, vineyards, raising farm animals, and a more relaxed way of life highlighted by a traditional afternoon siesta. Rather than focusing on the experiential contrasts between Spain and Boston, I think it is more beneficial to consider how the experience of the former has affected and enriched my living in the latter.

With completing the Camino de Santiago behind me, I do not think about what Boston does not have in comparison to Spanish cities and the Spanish countryside, but instead savor anew each attribute of Boston’s offerings as petite reminders of Spain, comparable to hors d'oeuvre examples of a full meal. Since I live in the Leather District, I am fortunate to readily enjoy many of Boston’s great amenities to help me recall experiences in Spain, especially from Boston’s multiple associations with Nature, such as: Boston Harbor and its connections to the sea and nearby destinations via ferries; the Charles River, Emerald Necklace, and Harborwalk pedestrian network; and the variety of numerous parks, both large and small, including: Boston Common, Public Garden, Copley Square, Post Office Square, and the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. Intimate-scaled street life comparable to Spanish cities such as Pamplona, Logroño, Burgos, and León can be imagined while strolling through Beacon Hill, Back Bay, and Harvard Square. So, while I had previously appreciated and enjoyed living in downtown Boston prior to walking the Camino de Santiago, I now value and enjoy the City more than ever, and have greatly extended my walks beyond the city limits to the surrounding suburbs of Brookline, Dorchester, Newton, and Watertown.

It is often said that the Camino eventually beckons former pilgrims to return for additional journeys. While I have toyed with the notion of returning to the wondrous rural environment of the Spanish countryside, I am less motivated by repeating the actual exercise in Spain than by harnessing my Camino experience as an inspiration and attitude towards the present while in Boston—or anywhere. Once again, the words of Eckhart Tolle provides an apt sense of feeling that also parallels Van Gennep’s condition regarding Aggregation upon completing a ritual journey:

- When we go into a forest that has not been interfered with by man, our thinking mind will see only disorder and chaos all around us. It won’t even be able to differentiate between life (good) and death (bad) anymore since everywhere new life grows out of rotting and decaying matter. Only if we are still enough inside and the noise of thinking subsides can we become aware that there is a hidden harmony here, a sacredness, a higher order in which everything has a perfect place and could not be other than what it is and the way it is.

- The mind is more comfortable in a landscaped park because it has been planned through thought; it has not grown organically. There is an order here that the mind can understand. In the forest, there is an incomprehensible order that to the mind looks like chaos. It is beyond the mental categories of good and bad. You cannot understand it through thought, but you can sense it when you let go of thought, become still and alert, and don't try to understand or explain. Only then can you be aware of the sacredness of the forest. As soon as you sense that hidden harmony, that sacredness, you realize you are not separate from it, and when you realize that, you become a conscious participant in it. In this way, nature can help you become aligned with the wholeness of life.

—Eckhart Tolle, A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose