In the 1980s, when Katarina Burin was six, she vacationed in Yugoslavia with her parents and brother. That’s how the artist remembers it. “We were in public spaces always, with other people. We’d eat together under a roof on a concrete platform every night.”

The reality was that the family fled communist Czechoslovakia and traveled from Yugoslavia to Croatia to Serbia, where they spent three months in a United Nations camp. “My parents . . . were stressed and paranoid. They didn’t tell us what was happening.” The family eventually resettled in Montreal, where her mother—who had been an architect—became a technical draftsperson; her father was an engineer.

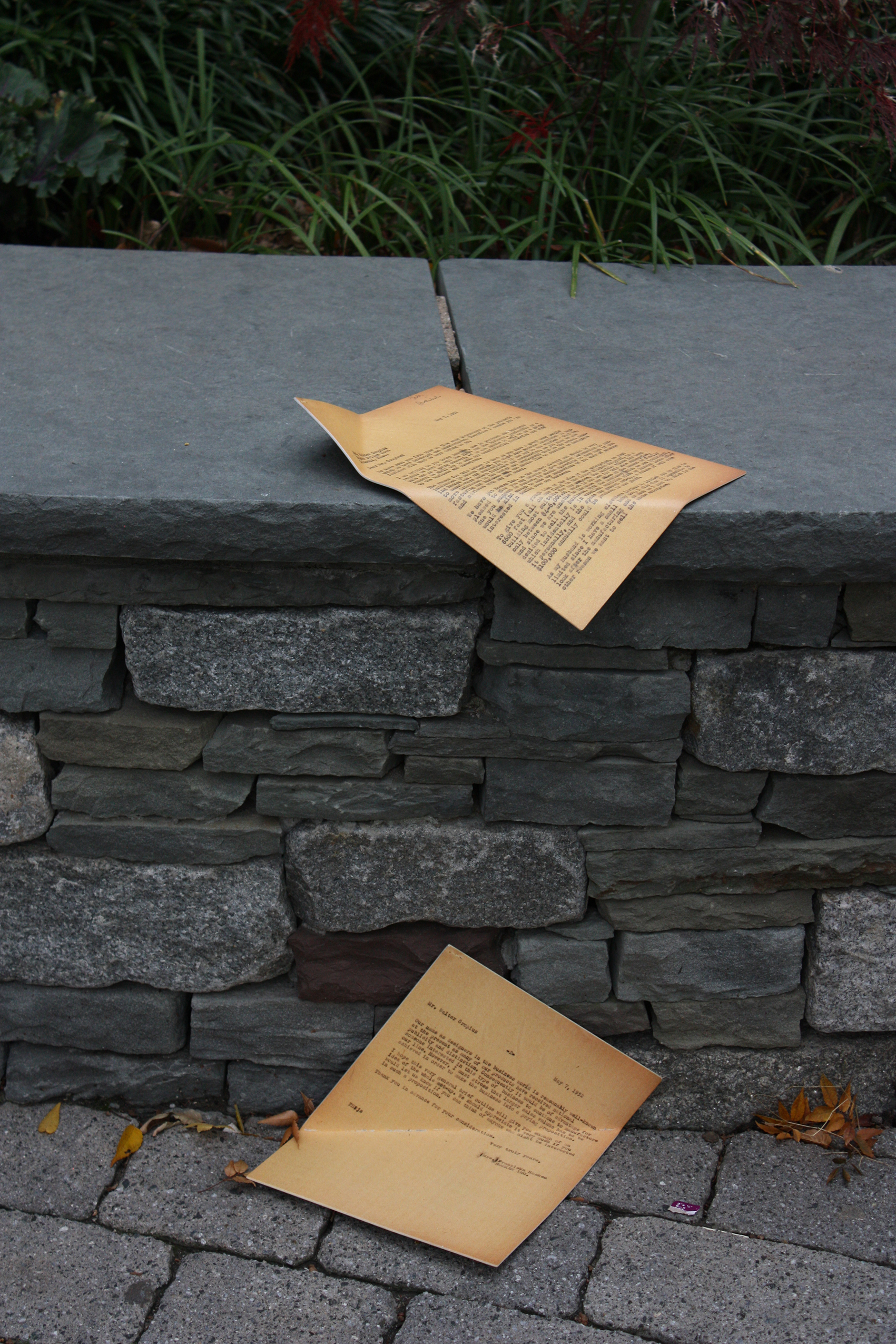

The strange collision of social and familial, exterior and interior, concrete public memorialization and ephemeral private memory that she associates with the camp drives her examination of everyday communist-era monuments in the exhibition Irrational Attachments, at Providence College—Galleries through March 14. Burin grew up to be an artist who taps into her parents’ skills to explore the heritage of midcentury European Modernism, a visual scholar who shuffles through archives like decks of cards.

Two months ago, in her studio at Harvard University, where she teaches, she’d made a prototype for the show: a cement planter with an inscription. She calls it an “anti-monument monument.” It resembles a Brutalist public marker.

“I want there to be a cheap, high/low feel,” Burin says. “Bridging the weird campground space with the civic/public space.” She shrugs. This project is only at its inception, and she’s not sure yet how it might evolve. Jamilee Lacy, director and chief curator of the Providence College—Galleries, has scheduled the show in the midst of a year of Bauhaus programming.

The exhibition reflects, Lacy says, “a toolbox the Soviet Union used to design public spaces as vacation spots, so you wouldn’t have to leave the country. . . . It’s quite dark.”