One associates the word Gesamtkunstwerk—“complete work of art”—with the wild, beautiful operas of Richard Wagner, which integrate music, theater, and imagery into spectacles that draw massive audiences a century and a half after their creation.

Could a restaurant be a Gesamtkunstwerk? One was: the Four Seasons, which opened in 1959, inside Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s famous Seagram Building in New York City. Its origin story is legendary. Liquor magnate Sam Bronfman, acting on the advice of his daughter Phyllis Lambert, hired Mies to design the company headquarters and wanted a restaurant for his tenants. “Mies didn’t want do it,” Lambert recalled in an interview. “Philip [Johnson, Mies’ partner on Seagram] designed the interior with lighting designer Richard Kelly, who had studied theater at Yale and provided a kind of theatrical aspect to the rooms. Mies would never have done that.”

In her 2012 book, Building Seagram, Lambert wrote: “With the Four Seasons, Philip achieved the ultimate Gesamtkunstwerk, in which theatrical interior effects are locked into reciprocity with Mies’s structural language.” No one disagrees with her.

Mies created the space, with his trademark clear-span architecture—not a column in view!—that afforded Johnson an unencumbered palette for his design. Johnson turned some of the architectural challenges into flights of imagination. For instance, the restaurant’s entrance faced sideways, to 52nd Street, not forward to front onto the magnificent, granite-slabbed plaza Mies created on Park Avenue. Another oddity: The Four Seasons, and its satellite Grill Room, sat one floor above the entrance, because 52nd Street slopes downward east of Park Avenue.

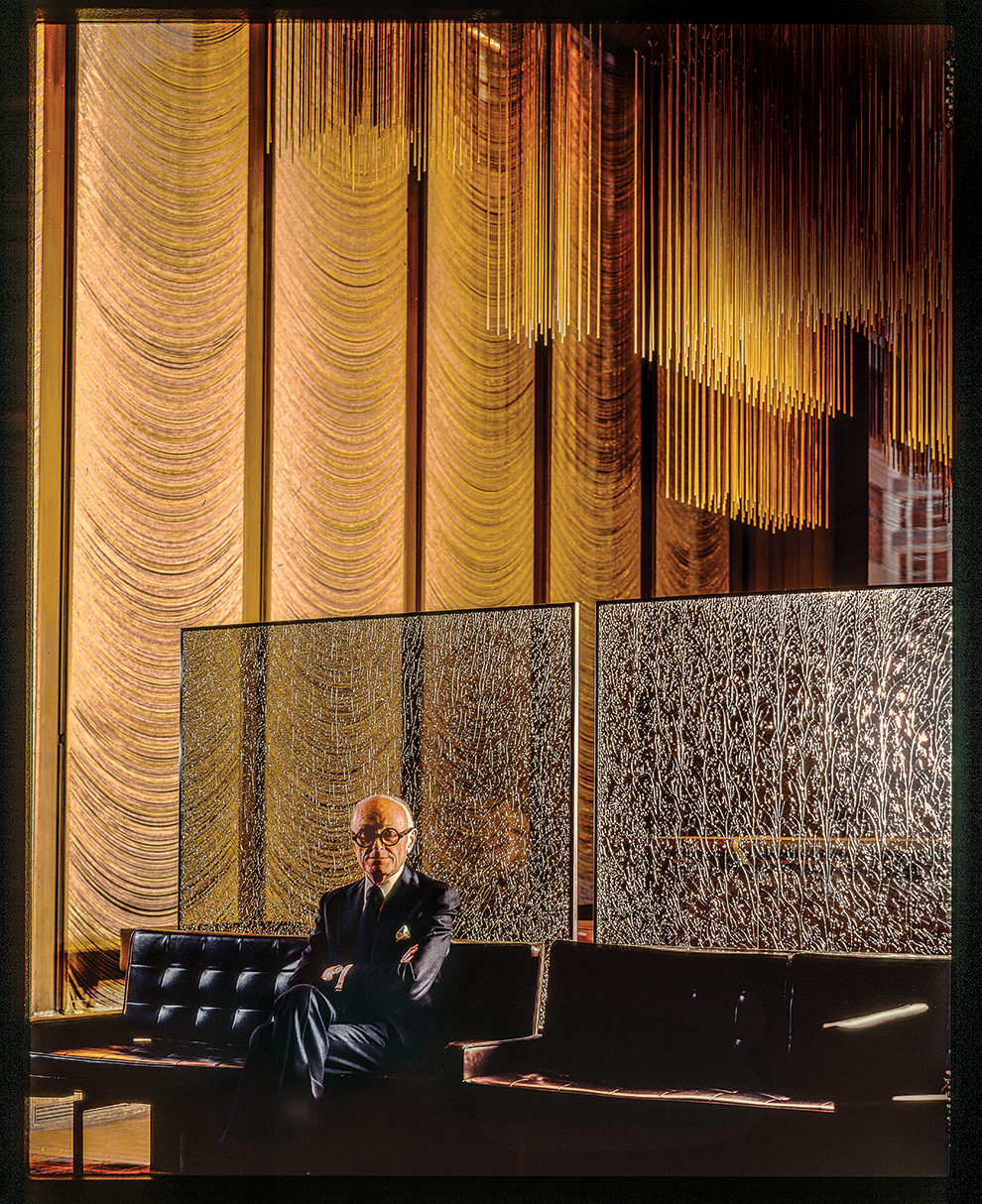

From these exigencies, Johnson created famous solutions, for example an elegant “Miesian” staircase that lifted visitors up to a storied promenade. To decorate the hallway connecting the main dining area and the grill, Johnson installed a monumental, 19-foot-by-20-foot theater curtain, Le Tricorne, which Pablo Picasso had originally designed for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Alighting from the staircase, the visitor encountered yet another famous work of art, the sculpture floating above the Grill Room bar. The unnamed sculpture, and its nearby twin in the Grill Room mezzanine, form two suspended layers of 8,000 gilt brass rods hanging from narrow wires. They are beautiful but also functional, lowering the 20-foot-tall ceiling to a more human proportion.

Mark Rothko agreed to contribute an original work for the mezzanine space overlooking the dining area but backed out. He later told journalist John Fischer that he accepted the assignment “with strictly malicious intentions. I hoped to paint something that would ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.”

Mies’ huge spaces presented a unique challenge, as Johnson explained to John Mariani and Alex von Bidder, authors of a 1999 book, The Four Seasons: A History of America’s Premier Restaurant. “Right from the start, I knew that the space was much too big for a restaurant. So really, I was just trying to fill the space somehow, stay true to Mies’s design for the building... There’s a lot of wasted space, you know. But there is in a great cathedral, too, isn’t there?”

David Hacin of Hacin + Associates in Boston first visited the Four Seasons when his father flew from their home in Switzerland to visit his college-age son. “It had this incredible processional,” he recalls. “You arrived at the lower level and then experienced this sense of drama and process moving through that space that was unlike any restaurant I had been to before.”