We live in the golden age of memorials.

I once would have written that line intending that it be read with a celebratory inflection. Now I mean it with a dose of irony, even a little sadness.

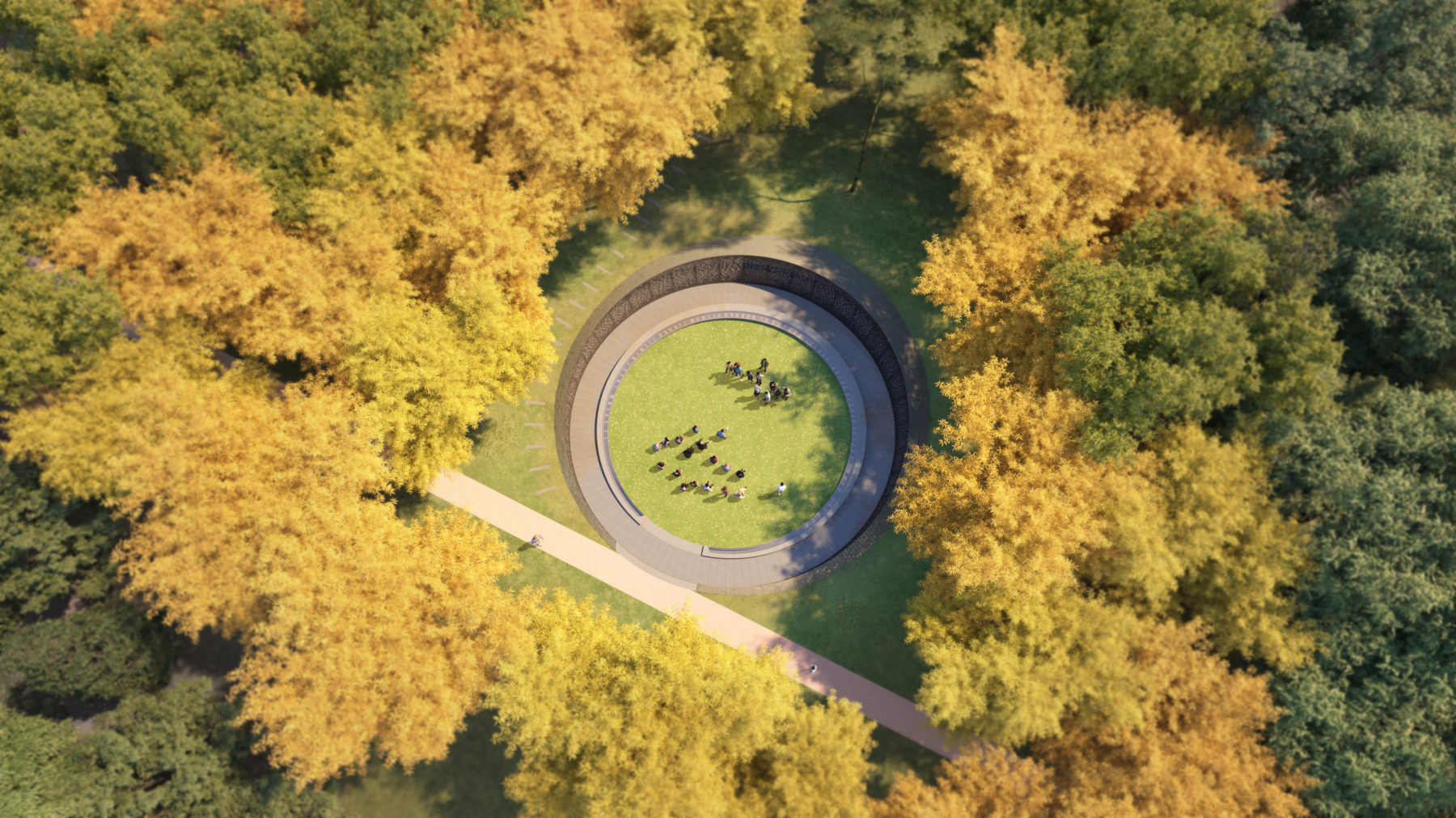

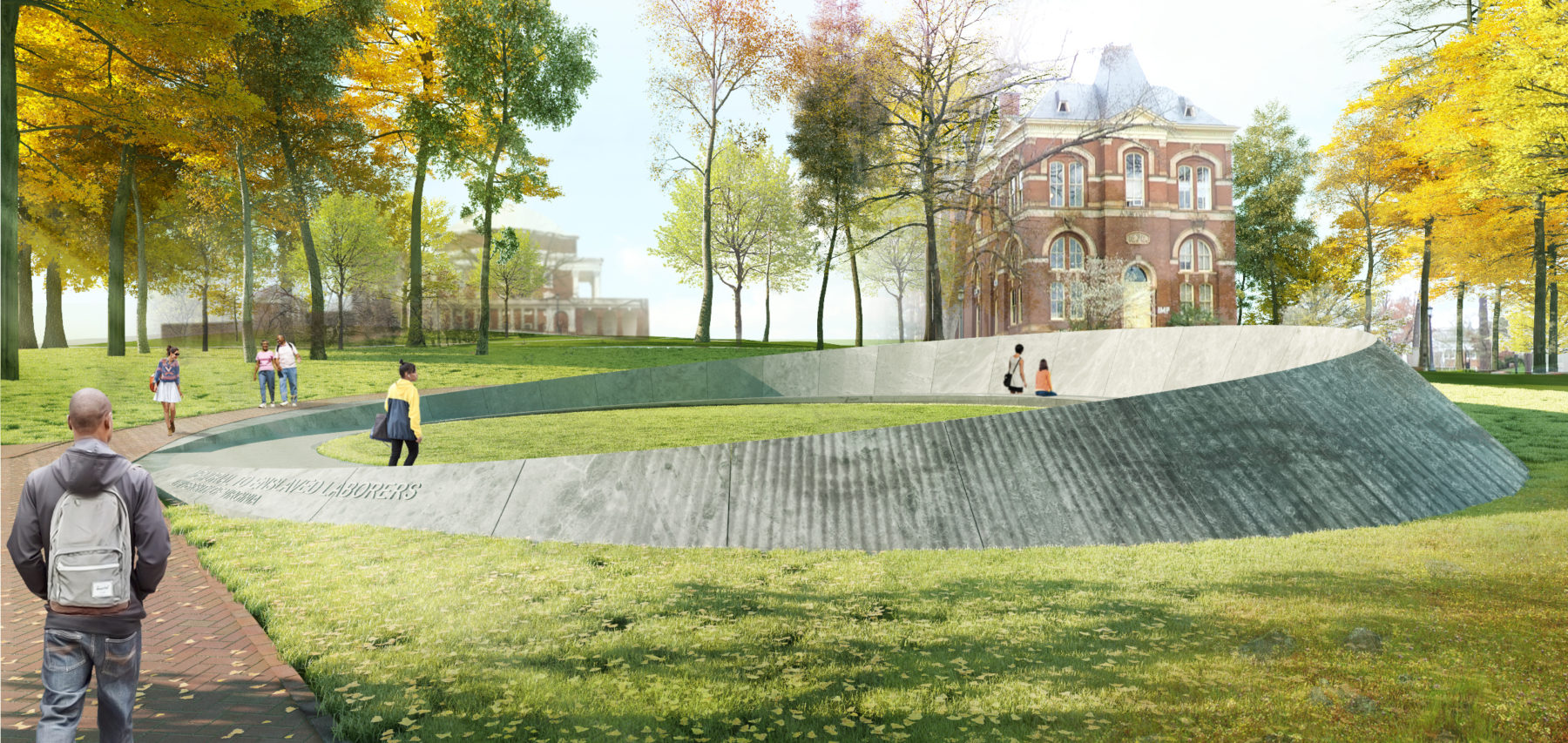

We have memorials that touch on an expanding range of topics, memorials of ever-greater creativity. Memorials put up, and memorials ripped down.

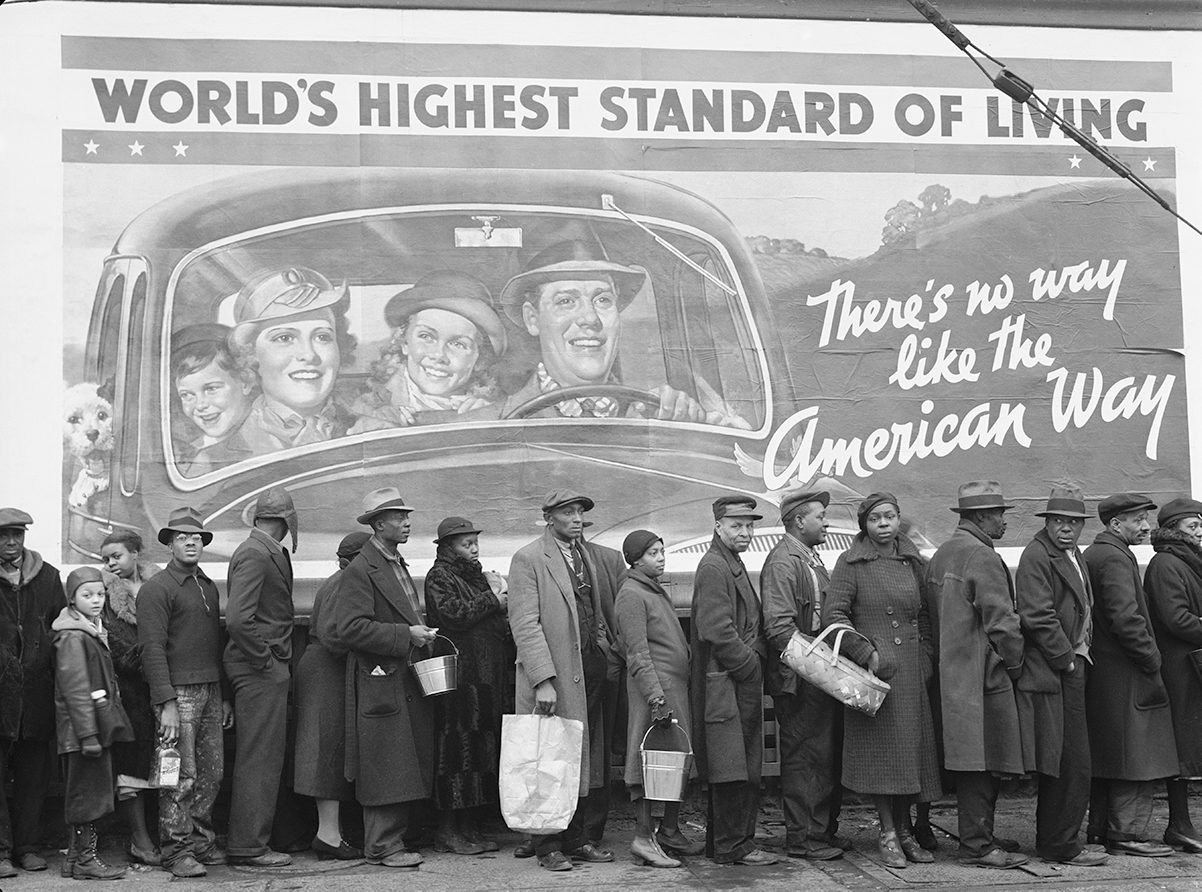

Shouldn’t we be nervous by our burgeoning memorial culture? Is it mere coincidence that memorials are proliferating in an era of intense inequality, growing violence, and heightened nationalism worldwide? We are mining our darkest history and celebrating our greatest individuals and achievements. But are we being inspired to change a fractured world? I hesitate to even suggest this: Do we avoid taking action in the world on behalf of our values, or against destructive elements, because we have increasing numbers of memorials in which to deposit these concerns? The words of Austrian writer Robert Musil should hang over our heads: “There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument.”

My thinking about our fervent public debate about memorials concerning African-American history was unstuck by a recent visit to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). Chance encounters with unexpected works of art can promote a dialogue in one’s mind. Look up, over the internal walls you have created between your thoughts, and you find that wisdom lies just over there.