Boston is a city that prides itself on having parks before there were parks. Boston Common, set aside in 1634 to graze cows, is credited as “America’s first public park.” One hundred thirty-five years ago, the city was also home to America’s first playground, when Frederick Law Olmsted designed and developed the Emerald Necklace—envisioning 1,100 continuous acres connecting major parks from the Common to Franklin Park and eventually Boston Harbor, along rivers, streams, and parkways. Olmsted’s parks were built to address issues of the day: increasing urban density, public health, flooding. These historic parks still provide some of what’s needed today, but we are facing new challenges. What can we do now that will set a new standard of excellence for our parks for the next 135 years?

In 2020, Boston is experiencing its most rapid population growth in nearly a century. Thanks to immigration, the populace is becoming increasingly younger and more ethnically diverse. The current tally is just under 700,000, and the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) projects 732,000 residents by 2030. With its increasing density and diversity, what does this city require to support the health and well-being of its citizens?

Boston is also experiencing the unprecedented effects of climate change, the existential threat of our generation. We are expecting the harbor’s high tides to rise by more than 3 feet by 2070. This is significant in a city where one-third of its land was once under water. We will experience déjà vu if Mayor Walsh’s Resilient Boston Harbor plan to protect against sea-level rise and climate change is not successfully implemented. Storms are increasing in frequency and volume of precipitation, and temperatures are rising. We could experience as many as 90 days with temperatures exceeding 90 degrees by the summer of 2070. These changes create serious challenges to our public health and economy.

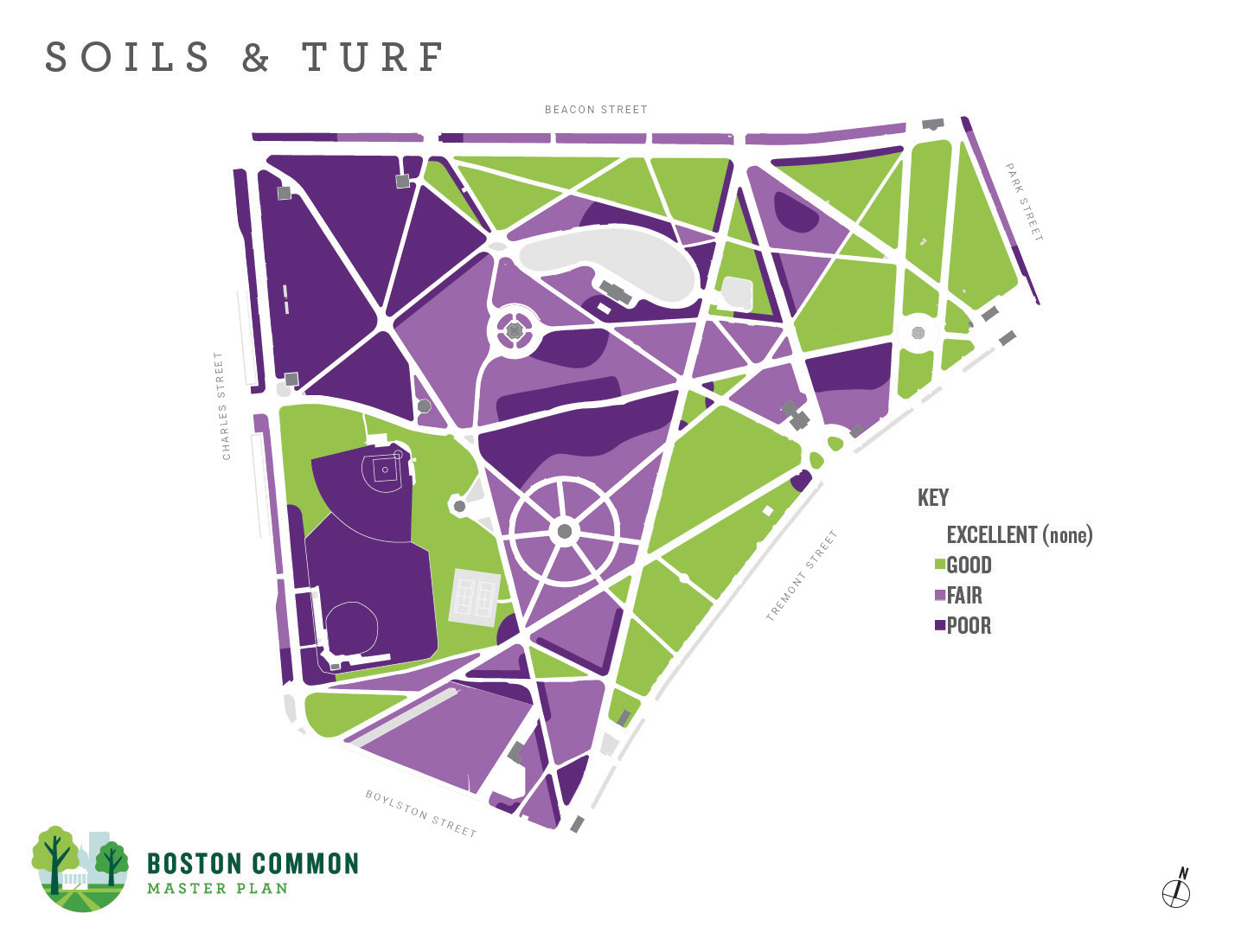

Image courtesy of Weston & Sampson

Cities around the globe are confounded by increasing land values and income inequality; Boston is no exception. Maintaining affordable housing and economic diversity is a struggle. Congested roads and underfunded public transportation challenge citizens and businesses. Our education system is failing many of our young people. What can we invest in today that will help to positively influence all these issues for our future?