Twenty years is a long life for a magazine—especially a nonprofit publication that doesn’t sell its soul for a handful of silver—but ArchitectureBoston also had a long gestation period of careful planning that gave the magazine a distinctive profile from the very first issue.

Our story begins on a crisp October weekend in 1994 on Martha’s Vineyard. This was the location of Future Search, a facilitated planning conference where 70 members of AIA New England met to grapple with the difficulties facing the design professions during those recession years of the early 1990s. Among the six major themes that emerged from the weekend, hosted by incoming Boston Society of Architects/AIA president Elizabeth S. Padjen FAIA, was a need for better communication with clients and the public. The BSA board created a communications task force to ensure that the ideas raised by Future Search didn’t just sit on a shelf. It took nearly four years of focused labor, but in June 1998, ArchitectureBoston was born.

Nearly 20 years later, six of the magazine’s founders gathered over lunch to recount its origin story and to reassert its values of independence, inclusiveness, and high standards. The magazine’s first art director, Judy Kohn, joined later in a phone interview. This discussion has been condensed and annotated by Renée Loth Hon. BSA, ArchitectureBoston’s current editor.

Elizabeth S. Padjen (founding editor): The magazine had actually been bubbling up over some period of time. The initial notion was that it was going to be a supplementary insert to the chapter newsletter. It was coming down to the idea that there would be issues of the magazine that would each be focused on a theme that was tied to our Future Search, themes the BSA board was aligned to. And the notion came up through this process that the various [BSA board] commissioners would serve as rotating guest editors for each of these issues.

Peter Kuttner (then–BSA president): This is what I had proposed. And Nancy [Jenner] and Richard [Fitzgerald] were horrified.

Padjen: I remember saying, in effect, “You guys are nuts.”

Kuttner: In those days, the board was structured somewhat differently, and we had these slightly Soviet-style commissioners on the board. We had a Commissioner of Education, a Commissioner of Design, a Commissioner of Research, and so on. It seemed they were ready-made for themes. It was even duller than that: Those themes would repeat each year.

First Issue: 1998 "Practice and Technology"

Padjen: Three themes survived through a couple of years, which were Practice and Technology, which later became Work; Society; and Design. Education was supposed to be the fourth, but I remember thinking, How dreary is that going to be? It was much later when we figured we could focus on —

Nancy Jenner (then–BSA deputy director and first publisher): We decided there would be a wild card instead.

Padjen: So the first wild card was the Waterfront issue.

Kuttner: And then we filled it with all wild cards.

Jenner: And we had [the trade show] BuildBoston [now ABX]. We had consultants and contractors interested in reaching our audience, a captive group of people who wanted to buy advertising. At the same time, we had this interest in longer articles, really meaty content; we could talk about bigger questions. So it was really a nice fit of all those things together.

Richard Fitzgerald (then–BSA executive director): I didn’t think solely about the magazine in terms of the magazine, but as part of a three-legged animal: the organization itself, the ChapterLetter, BuildBoston. Each fed one another, it seemed to me, financially and otherwise.

The team brainstormed scores of titles — ambitious, inclusive, definitely not self-serious — reflecting the magazine’s aspirations: Athens East; Gathering Places; Only Connect; Form and Dysfunction; Frozen Music.

Kuttner: For two years in a row, we had the discussion of: “If we had a magazine, what would it be?” The biggest fear, I think, particularly with the committee chairs at the time, was it not be a regional junior version of Record or Architect or something like that. New England Journal of Medicine was probably the biggest example that people keep popping up with, of something New Englandy and respected across the country.

A memo unearthed from the BSA archives with editorial assumptions for the nascent magazine is also instructive: Editorial autonomy from advertisers. Promotion of ideas and trends. No blatant self-promotion. No jargon. “Articles must have focus and avoid platitudes.”

Wilson Pollock (first chairman of the editorial board): While you guys were doing this conceptualizing of the magazine, I was up to my eyeballs in trying to hold a company [ADD Inc] together over in Cambridge. I got a call from Elizabeth [about serving on the first editorial board]. What was most interesting to me was that it was going to be a board assembled with nonarchitects and architects and people who were interesting to meet with. And I said, “Hmm, out of the bunker, let me just get over there.” My trips to Boston from Cambridge were something I looked forward to as much as almost any meeting I went to in those days.

Gretchen (Schneider) Rabinkin (among the first regular contributors): It was a venue to get out of the cave, so to speak, and to discuss ideas, even in the context of this professional organization. It was — and is — this fantastic forum for us to come together to talk about the ideas of our day, as well as the implications for making spaces.

I remember I had just graduated [from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design]. I was sitting down at the bottom of the stairs at Bruner/Cott; Elizabeth called me... I started with the Covering the Issues column and wrote that for I think 18 years. The magazine was not only my introduction to the BSA, but it was really my introduction to being an architect, to the profession.

2001 "Connections"

The magazine’s editorial advisory board has engaged more than 100 passionate volunteers over the years, for early-morning planning and critique sessions. One meeting in particular illustrates the board’s willingness to wade into contentious issues:

Padjen: We all showed up at an 8 o’clock editorial board meeting and [then–Boston mayor] Tom Menino had just announced that he wanted to sell off City Hall and build a new City Hall in the Seaport District. That was the conversation before the meeting settled down. It was Joan Goody [the late founder of Goody Clancy], I think, who said, “We should do an issue about this.” So we ended up tossing whatever the editorial calendar was and putting the focus on that. We invited half a dozen young firms to envision something different. And we said to them, “You’re going to get two pages. Show us whatever you want.” And what amazed me was how collaborative they were.

Pollock: I remember giving a seminar at the early BuildBoston. It was something like how to make a profit in architecture. I think it was sold out, it was so crowded. And we were sharing all the things that [our firm] did, that many architects just weren’t doing yet, in terms of how to manage your practice as a business. That was only done in a town like this, where people did open up and support each other.

Fitzgerald: I think for a layman like me, the density of talent in a small physical space like this city was overwhelming, delightfully. As Wilson said, the culture was already there, embedded in the small town of wise, well-educated architects. But the BSA provided a different kind of camaraderie that reinforced the ethic that was already here in the city. That’s manageable in a small city. Even though we had thousands of members, a lot of whom weren’t architects, it was pretty easy to get to know a lot of people. And it becomes family, even the ones you don’t like!

Rabinkin: I was just at City Hall with Maureen Anderson, who’s part of the public facilities department there, and she was previewing for me the new lighting strategy and lobby furniture that’s improving that public interface on the main floor. The BSA has become an accessible, open, reasonable partner with the City in thinking about what the future of City Hall and the Plaza might be. We hosted a forum here about it. That’s all still coming from that one issue — how we’re thinking about what this building is and what its landscape means for our city and for our region.

Advances in communications technology over 20 years have been dizzying. When the magazine first started, editors and contributors were still communicating by fax. But back then, the BSA was ahead of the technology curve.

Jenner: We had the first website for the AIA. That’s how we acquired architects.org. It was still very basic, and at that same time, we were thinking about redesigning the website, and e-mail was very nascent.

Padjen: I think it was 1995 when Internet Explorer was launched. So people were still trying to figure out, how do you use this thing?

Kuttner: Actually, going further back in digital history, before we were the first website in the AIA, we were the first bulletin board service. We had discovered a graphic version called First Class, and it allowed us to have little graphic icons. We enlisted Elizabeth, who was president that year, 1995, to have the president’s fireside chats. She had her own little folder, and our graphic was a little pyramid of folders, and they were the themes. [Three years before the magazine published], she was already sort of editing internal conversations among the members.

Jenner: When I first started at the BSA, which was in ’94, we were still sending out committee notices in #10 envelopes. And then we graduated to postcards.

Judy Kohn (first art director): We had no photo budget. We did what we could with what we had on hand, what we could get from friendly photographers, what I could do with my camera when things got desperate. For the magazine covers, we deliberately stayed away from architectural images. The idea was we would use some kind of abstract fragment of something. We would use bars of gold or pieces of bridges, all sorts of odds and ends that were nonspecific. Because the audience was mostly architects, it seemed like a good way to appeal to all of them while not offending any of them by not including every member on the cover at some point.

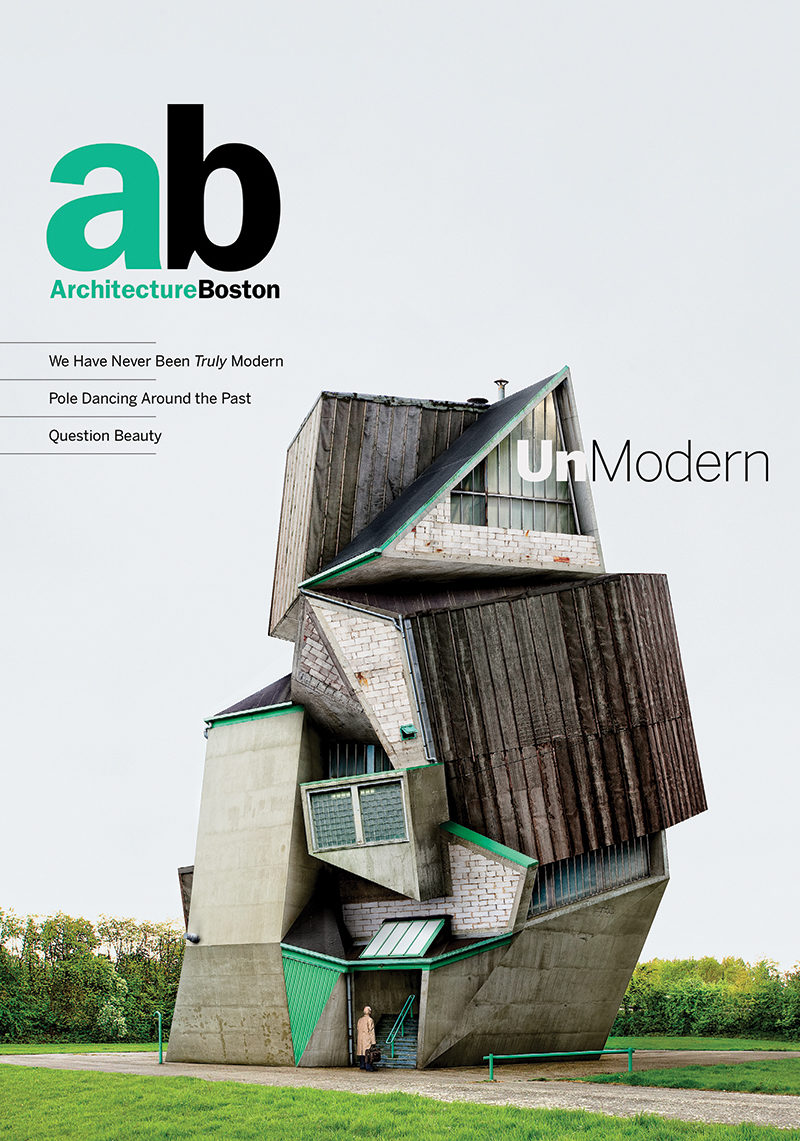

2010 "Unmodern"

Indeed, one of the magazine’s distinguishing characteristics from the start has been its editorial independence, both from advertisers and most chapter activities. It’s a big part of what makes ArchitectureBoston so unlike other AIA publications.

Padjen [recalling an early article submission from a prominent member that did not make the grade]: I remember being really, really upset and talking to Richard in his role as father confessor, as he has served architects for many years. And Richard gave me permission to kill it. And it was in the first issue. It was the most liberating thing you can imagine. It was the right thing to do. But it also established something for me — maybe a sense of my own authority, but also I knew that we were onto something that was important to us. We were going to hold to certain standards.

Pollock: Richard, you were ahead of your time in terms of empowerment. You stood by her and supported her at a critical time. You might not have even realized how critical it was.

Over 20 years, one thing that has not changed is the mission outlined by Padjen when the magazine debuted: “ ...to expand both professional and public understanding of architecture by encouraging, even provoking, a broader discussion of the built environment, one that respectfully includes all voices.”

Jenner: We would go to the national convention and places around the country, and everyone always wanted to know, “How do we do it? How are you able to publish a magazine and have a trade show and have so many members, more members than any chapter?” It came down to this fundamental principle of being inclusive, and not being protectionist, which is what trade associations often were. The idea of allowing a fluidity of voices and welcoming everyone in — people would ask, “You let nonarchitects come to BSA meetings?” And we said, “Yes, and we feed them lunch.’’

I think that with ArchitectureBoston, so much of what we did came from that sense of creating a dialogue that’s about a shared vision. Because architects don’t exist in a vacuum. They need clients, and they need contractors, and they need subcontractors, and they need people to help them market. It’s a much bigger world.

The BSA’s “Big Tent” philosophy, reflected in the magazine, brings a crucial perspective to what might otherwise be an insular trade journal. Padjen remembers one example from the magazine’s second issue:

Padjen: It was a piece on [Boston’s] Holocaust Memorial. I had invited Marcie Hershman to write about that; she had just written a book called Tales of the Master Race, which was about the Holocaust. The Memorial had been really controversial in terms of its siting [at Faneuil Hall marketplace]. And I was one of the people who thought, “Yeah, great, but there it is in front of one of the oldest parts of the city, and wouldn’t it be better to put it out at Fort Point with the Federal Courthouse?” Her story changed my mind. It was reading that piece, where she says, “History happens in the center of things. It happens while you’re buying flowers.” I thought, “She’s right. This is the perfect place for this memorial.’’ It’s the power of words to change your thinking; in 600 words, to change what had been, on my part, a really strong opinion.

Kohn: The magazine’s strength is the way it manages to underscore a sense of community among the members of the BSA and to keep the community talking about both architecture issues and Boston issues. It’s a tool in good times and bad times. Architecture is a profession that responds so much to the economy; they’re either booming or they’re starving. [Yet] they manage to keep interested and engaged in the conversation, talking about ethics, values, the big-picture items.

Padjen: Over time, a lot of people, I discovered, felt a sense of ownership because they had participated in some way, even if they hadn’t necessarily written for it.

Kuttner: You can go national anywhere within the AIA. People everywhere in the country talk about it.

Pollock: No other chapter has anything like it.