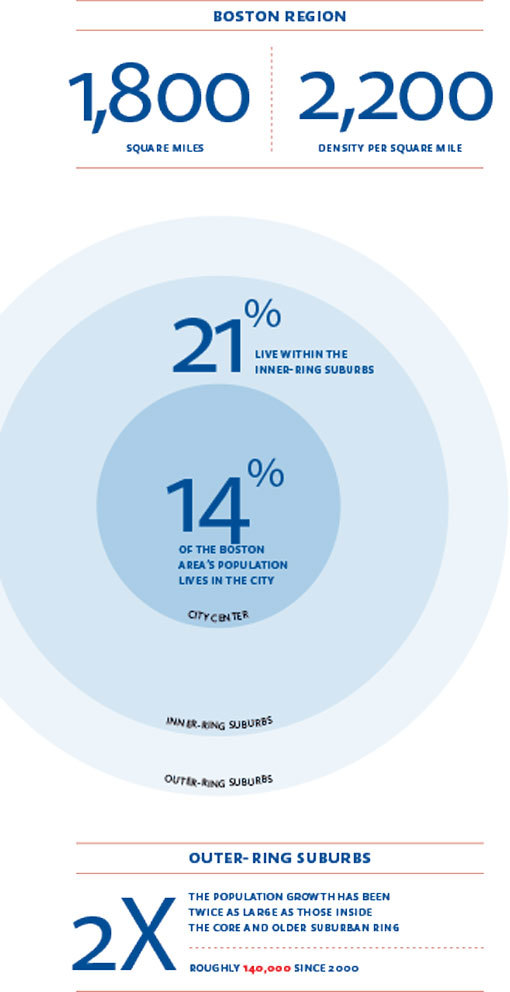

The Boston media and academic communities hail the region as densely urban, making it all but irresistible for millennials. This penchant for urbanity would be news for roughly two-thirds of the regional population, and for most young people as well. Nor is the area particularly dense by national standards. Indeed, among the nation’s 41 urban areas where the population numbers more than 1 million, the Boston region, which now extends to New Hampshire and Rhode Island, ranks only 33rd. Spread over 1,800 square miles, this region has a density of 2,200 per square mile; in contrast, the density in the Los Angeles urban area, where I live, is 7,000 per square mile.

Boston is somewhat less dense than Sun Belt urban areas such as Las Vegas; Miami; San Diego; and San Jose, California, and significantly less dense than rapidly expanding urban areas in Texas. Visitors to Boston, from either the rest of the country or around the world, can be forgiven for thinking the region exists primarily between Logan Airport and the Back Bay. Planners, the media, and academics have a far less reasonable excuse.

Most Boston-area residents live in what planners demean as “mindless sprawl.” Although there has been some small increase in the share of the inner core of the region, suburbanization continues to dominate. Since 2000, the population growth in the outer rings — roughly 140,000 — has been twice as large as those inside the core and older suburban ring.

The real problem here is demographic stagnation, brought in large part by high housing prices. Like other legacy cities — those whose structure predates the automobile era — Boston’s inner ring is becoming something akin to a gated community. In the City of Boston, the cost of living is nearly 40 percent above the US average. Condo prices have been soaring, including in lower-cost neighborhoods such as Dorchester and Roxbury. Overall, housing affordability adjusted for income is almost 1.5 times as high in Greater Boston than in key competitor regions such as Raleigh, North Carolina.

Expensive, thriving urban centers are wonderful for many things — architecture, the arts, good restaurants. They are not so good for middle-class families.

As Boston’s suburban growth has slowed and prices have stayed high, families are increasingly out of fashion. Of the nation’s 52 metropolitan areas with more than 1 million residents, the Boston urban area now has the 47th lowest percentage of population aged 5 to 14 (12.1 percent) in comparison with more affordable areas such as Salt Lake City, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, and Raleigh (15 percent or higher).

This phenomena parallels another — rapid aging. The generations who settled in the region beyond Route 128 and Interstate 495, as well as those in the older suburbs, are becoming NORCS, or naturally occurring retirement communities. Of the 52 major metropolitan areas, Boston now has the 12th highest percentage of seniors over 65. By the end of this year, the Massachusetts Council on Aging estimates that the number of adults aged 60 and older in the “granny state” will be greater for the first time in recorded history than the number of children aged 20 and younger.

Boston boosters gush over the large presence of educated millennials, no surprise in the western world’s premier college town. Yet suburbs, particularly over time, matter to them, too. Nationally, most educated people aged 25 to 34 don’t end up in the urban core — three times as many settle in the suburbs or exurbs. High prices and the lack of an affordable suburban housing stock may explain why Boston’s millennial surge has begun to slow. Between 2011 and 2013, the growth among 25- to 34-year-old college-educated people was among the lowest of any in the country, up just 6.3 percent. That is barely half the rate for Nashville, Tennessee; Orlando, Florida; and Denver, and well below the growth in Cleveland and the big Texas cities (more than 10 percent).

Conventional wisdom insists that young people prefer the city and will want to stay there. But economist Jed Kolko noted last year in a Huffington Post article headlined “Urban headwinds, suburban tailwinds” that the percentage living in the inner city drops precipitously as they enter their 30s and continues to drop for decades. For most young people, dense urbanity represents a transitional stage.

Due to preferences or economic realities, surveys indicate that most millennials will end up as suburbanites. Research by such groups as Frank Magid and Associates, the National Association of Realtors, Nielsen, and even the Urban Land Institute all indicate that most millennials are destined to head to the burbs.

Last year, the National Association of Realtors found that 83 percent of millennials’ home purchases were single-family detached. So, as they start families, the suburbs are likely to remain “the nurseries of the nation.”

What do these trends portend for Boston? To be sure, the region will be able to continue to attract “the best and brightest,” and powerful companies seeking elite help, such as General Electric, can continue to find the young, urban-dwelling, well-educated staff they crave. They may even pay them enough to perhaps secure a decent apartment along an MBTA line.

This leaves little space for anyone — except the young and hip, the well-to-do, and the childless. Most outside this charmed circle will live meagerly. No surprise that many continue to leave the metropolitan area, which has lost 250,000 net domestic migrants since 2000.

This scenario may please those who dream of a city lined with expensive high-rise apartment towers and filled with one-bedroom condos or studios that few families will want and many cannot afford. But it obliterates the prospects of homeownership for aspiring middle-class families. Boston’s sprawl could prove a vast field of opportunity — whether in the close-in streetcar suburbs built at the turn of the century or the much lamented postwar and 1980s boom tract houses. The region’s priced-out millennials are already spreading into working-class suburbs, such as Somerville, as well as Waltham and Medford. In the outer rings, however, there may be room, given the often extremely strict zoning, to relax one- or two-acre limits. Much of the country provides an excellent suburban quality of life at the fraction of that density.

The region needs to accommodate people when they leave their bar-hopping days and start shopping at Target and buying strollers. Does that mean we should turn the region into a snowbound replica of Houston? No, but there are things that can be learned from places that accept both “sprawl” and multipolar economies. Greater Boston should consider developing affordable suburbs like Houston’s Cinco Ranch, Sugarland, or the Woodlands, which offer good schools, parks, bike paths, and town centers. Nor would it be tragic if both older suburbs and newer ones develop their economies so not everything requires a commute into the densest part of town.

This message, no doubt, will infuriate those who feel cities are about reviving something that resembles, in form but not familial essence, the city of the 19th century. Boston is not just the charming old city or the exclusive inner suburbs such as Lincoln and Newton; it is also Revere, Framingham, and Waltham.

Ultimately, a city’s heart is not just in its center but wherever its people choose to settle. “After all is said and done, he — the citizen — is really the city,” observed Frank Lloyd Wright. “The city is going wherever he goes.”