Steve Imrich FAIA

Name: Steve Imrich FAIA, LEED AP BD+C

Job title and company: Principal, Cambridge Seven Associates (C7A)

Degree(s): MArch, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); BA, Goddard College

Professional interests: Cities, communities, public architecture, art, culture, and nature.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a new business school for the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Lowell North Campus Innovation District and a new Children’s Zoo at the Franklin Park Zoo along with various renovations at the Museum of Science in Boston.

Above: UMass Lowell Pulichino Tong Business Building. Image courtesy of Cambridge Seven Associates.

How do (or how did) you explain to your mom what you do for a living?

I’d have to focus on the most creative parts of what I do because my mom was a pretty artsy, edgy lady without much tolerance for the perfunctory or mundane. I’d tell her that getting paid to think about making architecture is a luxury that most folks can only dream about, and that that our kids can see and experience something exciting and tangible for our efforts. I’d steer clear of explaining the daily routine or how much time I spend on the phone and computer, because she’d be perplexed by that!

What inspired you today?

I paint in my free time so I’m inspired by just observing the sky and light on almost any day. I was also captivated by a radio program today related to aesthetics and ”the origins of beauty” from an evolutionary biology standpoint. Since design involves opinions about many subjective topics, it’s fascinating to understand that the role of ”beauty” in nature is not so subjective. After thousands of years of evolution, we’re just beginning to understand the relationship between natural systems and what we build. The program featured scientist and author Richard Prum who postulates that “…art consists of a form of communication (in nature) that coevolves with its own evaluation.” I think this emergent quality of art is relevant to architecture and I’m excited to follow this thread further.

What architectural buzzword would you kill?

I have a hard time with the way many folks overuse ”breaking up the mass.” I know that buildings can be too monolithic or boring sometimes, but we seem to be in a period where random articulation is more of a danger. I prefer to think of how projects build variety into their composed expression rather than ”breaking” things.

When you’re working, do you discuss or exchange ideas with your colleagues?

Having private, contemplative time to think through complex issues is important, but in my opinion no idea worth developing has ever moved forward in complete isolation. Every idea has a history and context, and interactions with others seem to facilitate more complete and relevant results.

What are you reading?

I just finished a great series of essays about the effects of technology on culture by Sven Birkerts called Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age. It’s an insightful but somewhat alarming series of sketches covering how our wiring is altered by the wild west of social media, amongst other things. I’m also halfway through a biography about Dorothea Lange. She had an interesting sideways entry into the world of documenting personal stories about the US after the Depression in the 1930s. Lange seems to have lived the contradictions inherent in the promise of the “American Dream” through her photographs. Her work process also raised some interesting questions about authenticity in the arts that would apply to architecture, too, since she was a proponent of visual manipulation to produce a desired meaning. I had no idea that some of her most iconic photographs were staged and altered, but many contend that it doesn’t take away from their cultural meaning and power. She was a big fan of the Chinese proverb that says, “The eyes are blind to what the mind does not see.”

Do you sketch by hand or digitally?

I first learned about digital drawing on a program called Drawbase in the 1990s, but as soon as we changed software to AutoCAD and Revit I went back to mostly hand sketching. Hand drawing involves risk that digital drawing sometimes eliminates or camouflages. In some cases, that’s a big benefit because the digital process evens out irregularities, but if not policed it can kill the desired meaning of a drawing. For folks who focused on hand drawing in their early education, the computer presents an awkward interface, but I think that’s changing as younger designers grow up with the tool and as the software interfaces become more intuitive.

Has your career taken you anywhere you didn’t expect?

When I started thinking about architecture as a career, my focus was actually on housing and community design. I was a VISTA volunteer at the Pittsburgh Architects Workshop in Oakland in the 1970s, and after the turmoil of the 1960s many communities needed to rebuild entire districts, including parks and commercial and recreational areas in addition to just basic housing. With my art background, I was involved in community mural and playground developments as well as mapping and planning exercises. Ironically, for most of my modern career and time at C7A, I’ve ended up concentrating on public museum and university work. I’ve also had the opportunity to travel and work in places that I never imagined I would. Working in Kuwait on The Scientific Center and then moving around the country to places like Tennessee and Alaska was pretty exotic for a small town Western Pennsylvania boy. I’m still very interested in the public realm, and I like the optimism of architecture and the way it engages the general public. My path has changed but the basic interests are the same.

Above: Tennessee Aquarium and Ross’s Landing development. Photo: Nick Wheeler.

Where is the field of architecture headed?

We’re getting to the point with technology and materials where just about anything is possible to build, so the big question is why. Understanding the connections between human experiences and architecture will involve more interesting rationalizations since the possibilities are limitless. I can’t help but think the key to successful future environments relates more to the strength of the connective landscape than to buildings. We have very little left in the world that is not designed, but I think that most people still perceive the space in between buildings as residual rather than designed. It just takes one trip to the High Line in New York or some other great urban space to realize the power of designed landscape, and even the greatest building is lonely if deposited in an inappropriate fabric. This idea is not new, but I’d like to think we will become more successful in blurring the distinctions between building, landscape, interiors, art, and nature in our work.

Above: New England Aquarium Giant Ocean Tank renovation. Photo: Kwesi Budu-Arthur/C7A.

Can design save the world?

A different way to think about this question may be to consider whether the world can afford to not be designed. Individuals’ actions shape or modify our environments, whether intentional or not. Of course, people need to carefully consider their personal relationship to the world, and everything that we make has a strong influence on how we survive, thrive, or obtain some kind of happiness from living, but thoughtful consideration about how to influence our time on the planet makes sense to me. Professional designers have an incredible opportunity—and added responsibility, in my opinion—to make wise choices.

Above: Parker River National Wildlife Refuge headquarters, Newburyport, Massachusetts. Photo by Kwesi Budu-Arthur/C7A.

What do you hope to contribute from your work?

I hope I’ve made some minor contributions to the environment and cultural enrichment through the projects that have come my way. Working with teams and continuing to make uplifting experiences and pleasant surprises in public places is very gratifying to me. I’ve had the privilege over my career to work with some great clients—such as the New England Aquarium and the Boston Children’s Museum—and some wonderful projects, so hopefully the streak will continue. I’ve been very lucky.

Who or what deserves credit for your success?

So many people have guided me or kept me out of trouble over time, starting with Sister Mary Jane, my high school art teacher! The joy and influence of my wife and kids have big sway, and a group of lifelong friends going back to my college days and the times at the Pittsburgh Architects Workshop were pretty influential. My teachers in graduate school were persuasive as well. Jan Wampler FAIA at MIT gave me a big break when I worked in his office as I was completing school. He introduced me to Aldo and Hannie van Eyck, who were my idols even before I went to graduate school. I had no idea that I’d get to meet them personally, but they were friends of Jan and stayed with him when they were in town. I spent an hour stuck in Sumner Tunnel traffic once with Aldo when Jan asked me to pick him up at the airport. It was like having a personal seminar with Einstein. I’m also very fortunate to have worked with many of the early stars at C7A, including some of the original partners as well as the younger and up-and-coming talents that give C7A its current energy.

Your least favorite college class?

That’s a hard question. I don’t recall having had a subject that I didn’t like, but there were ”hard” professors. I went to a very small college with classes that were never bigger than about ten people. It’s hard to be disengaged in that kind of situation, so even with some of the more challenging subjects for me, like statistics, it still worked out. There may be a few teachers who would have made the list of ”hard” or ”least favorite,” but I’ll leave it at that.

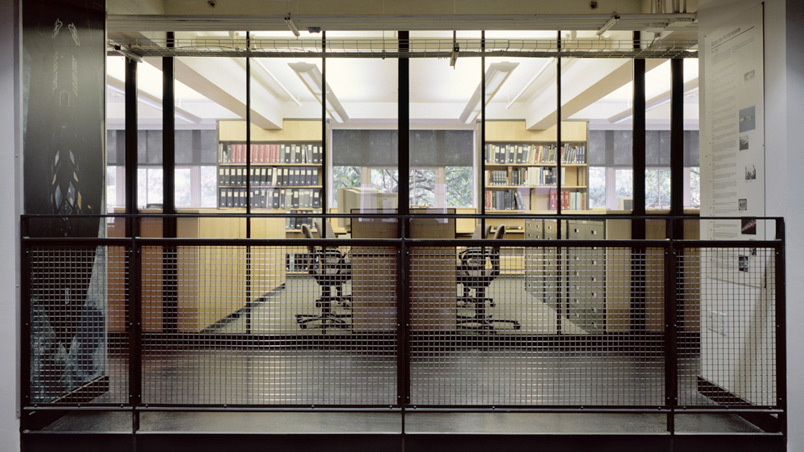

Above: MIT Complex Systems Lab. Photo by Nick Wheeler.

If you could give the you-of-10-years-ago advice, what would it be?

Relax, and let the mystery be! Designing and making buildings can be a long, stressful process, since most of the time the amounts of money to build buildings is formidable, and it makes everyone nervous. Somehow, it all generally works out even though everyone sweats the details in the middle of the process.

Your favorite Boston-area structure?

Like music, it’s impossible for me to have just one favorite, but here are some places that resonate with me: Alvar Aalto’s Baker Hall; Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel; Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace; Hugh Stubbins & Associates’ Federal Reserve Bank of Boston; I. M. Pei & Partners’ Hancock Tower; World’s End;, Foster + Partners’ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston expansion; Willard T. Sears’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum; Joppa Flats; Henry Hobson Richardson’s Trinity Church; Van Brunt & Howe’s Cambridge Public Library with Ann Beha Architects’ renovation and William Rawn Associates’ expansion; Anmahian Winton Architects’ Community Rowing Boathouse; Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; and Rail Trails.

Who would you like the BSA to interview next?

Hearing from the younger designers and including environmental artists and industrial and landscape designers would be great.

If you were on a late-night TV show, what would your 30-second plug be?

Figure out a way to make things better for people and be happy doing it. Everyone has obstacles, but if you’re handy and have a good attitude, that goes a long way. I heard somewhere that there are only three important things to remember for a good life: don’t be cruel, be artistic, and have a sense of humor. I think those are pretty good!

If you could sum up your outlook on life in a bumper sticker, what would it say?

One of my professors had a catchy saying that’s stuck with me over the years: “Nothing you do is what you think!”