“The ultimate aim of all visual arts,” Walter Gropius wrote in his Proclamation of the Bauhaus in 1919, “is the complete building.”

His encompassing aesthetic merited a manifesto. He was playing with German philosopher K.F.E. Trahndorff’s idea from the previous century, Gesamtkunstwerk—total work of art. This year is the legendary German design school’s centennial, and it’s being feted with exhibitions, books, and events. Gropius, an architect, was the school’s founding director. In his vision, fine art, architecture, textiles, tea services, and typefaces all struck harmonizing notes. Art entwined with industry.

After World War I, Gropius saw design as a means to leave the pain and relics of the past behind and strive to make a more humane world. His aesthetic wasn’t merely about image and consonance; it was about how to live rationally, pragmatically, and creatively. It shaped a century, and it still holds sway today.

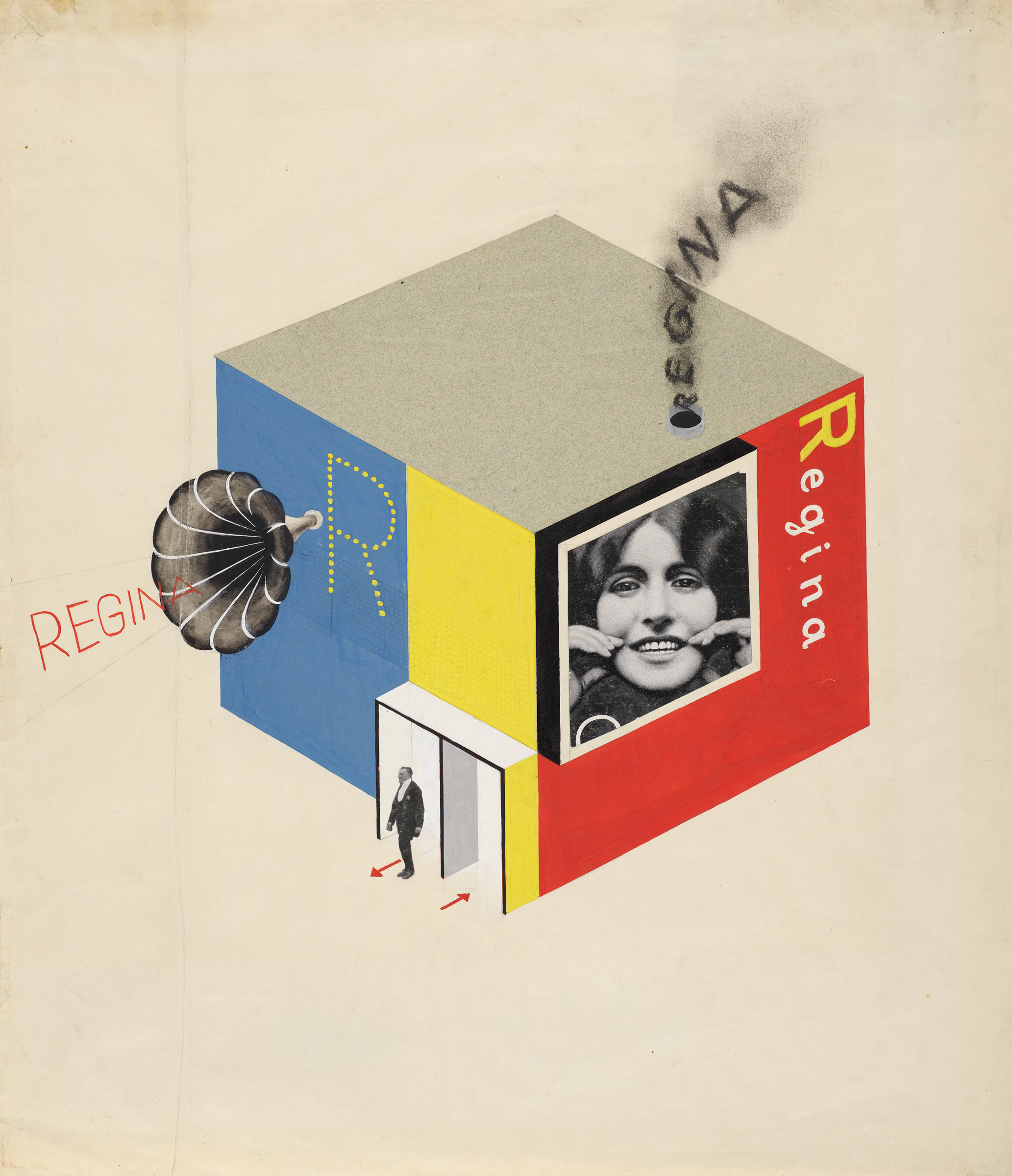

“The complete building” notwithstanding, the school, based in Weimar, Germany, didn’t offer an official course in architecture until 1927. But everything, one way or the other, aimed students in that direction. Bauhaus teachers such as László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers pared art and design down to essentials—form, material, color—and prodded students to use them with grand inventiveness and hard-boiled practicality.

The Bauhaus and Harvard, an exacting and expansive exhibition of mostly small-scale works at the Harvard Art Museums through July 28, dips into the largest Bauhaus collection outside Germany, at Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum. It recounts the Bauhaus’ rise and fall, and the school’s ties to Harvard.