Many of us have probably tried a sauna at some point in our lives—perhaps at a gym or spa, where the experience may be miles removed from the practice’s cultural origins and significance. It’s rare to come across a traditional sauna, yet Greater Boston happens to be dotted with them.

Illustration by Alyson Fletcher

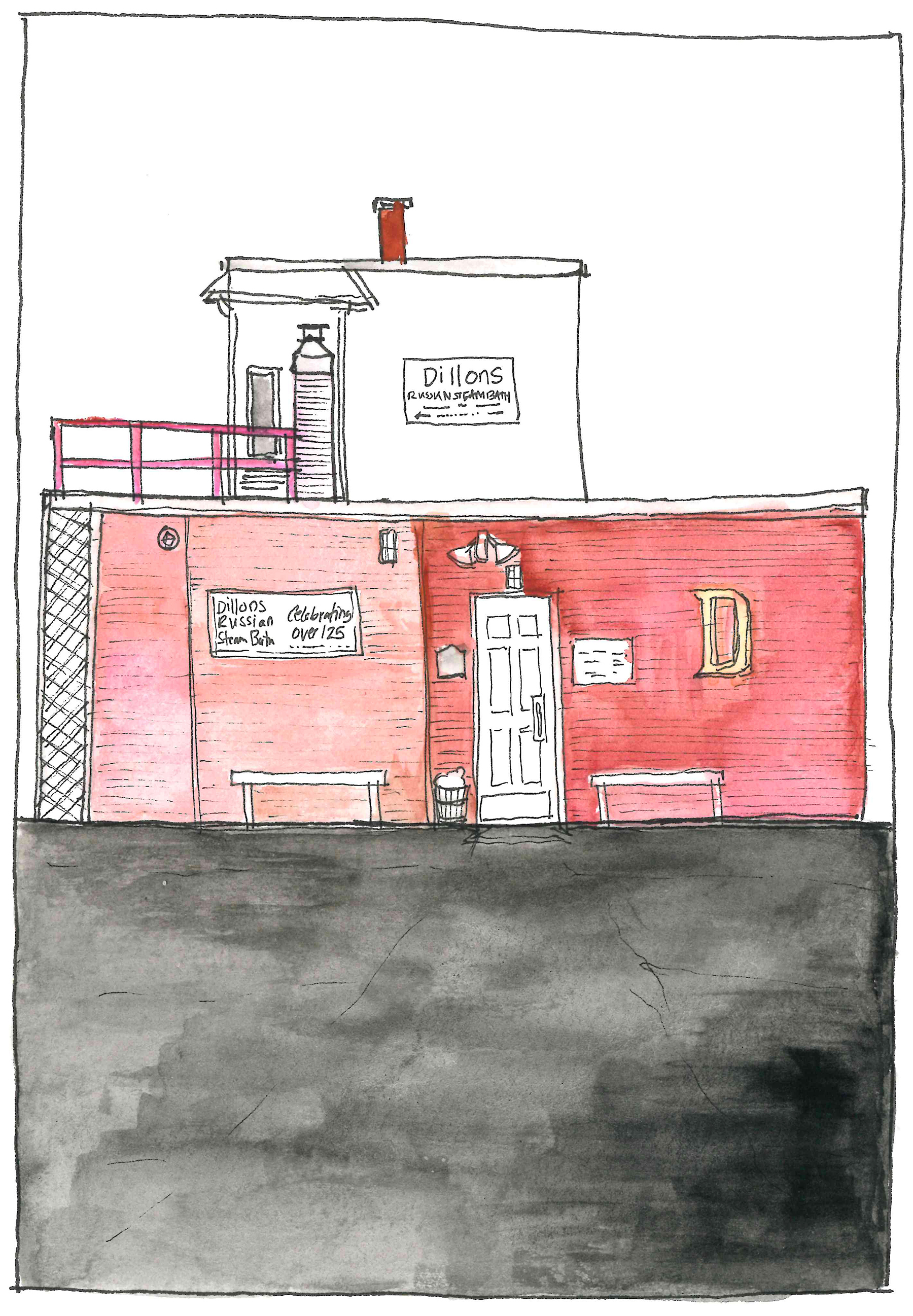

While conducting fieldwork for a plan for Chelsea’s downtown streets a couple years ago, I stumbled upon Dillons Russian Steam Bath. It seemed rather out of place in the heart of a city with a largely Hispanic and Latino population, but between the late 1800s and the 1930s, Chelsea had been a primary destination for Russian-Jewish immigrants, and sauna was one of the traditions that survived their resettlement. Even though demographics have changed with time, these Chelsea baths have been in operation since 1885, with the business laying claim to being the oldest steam bath in America.

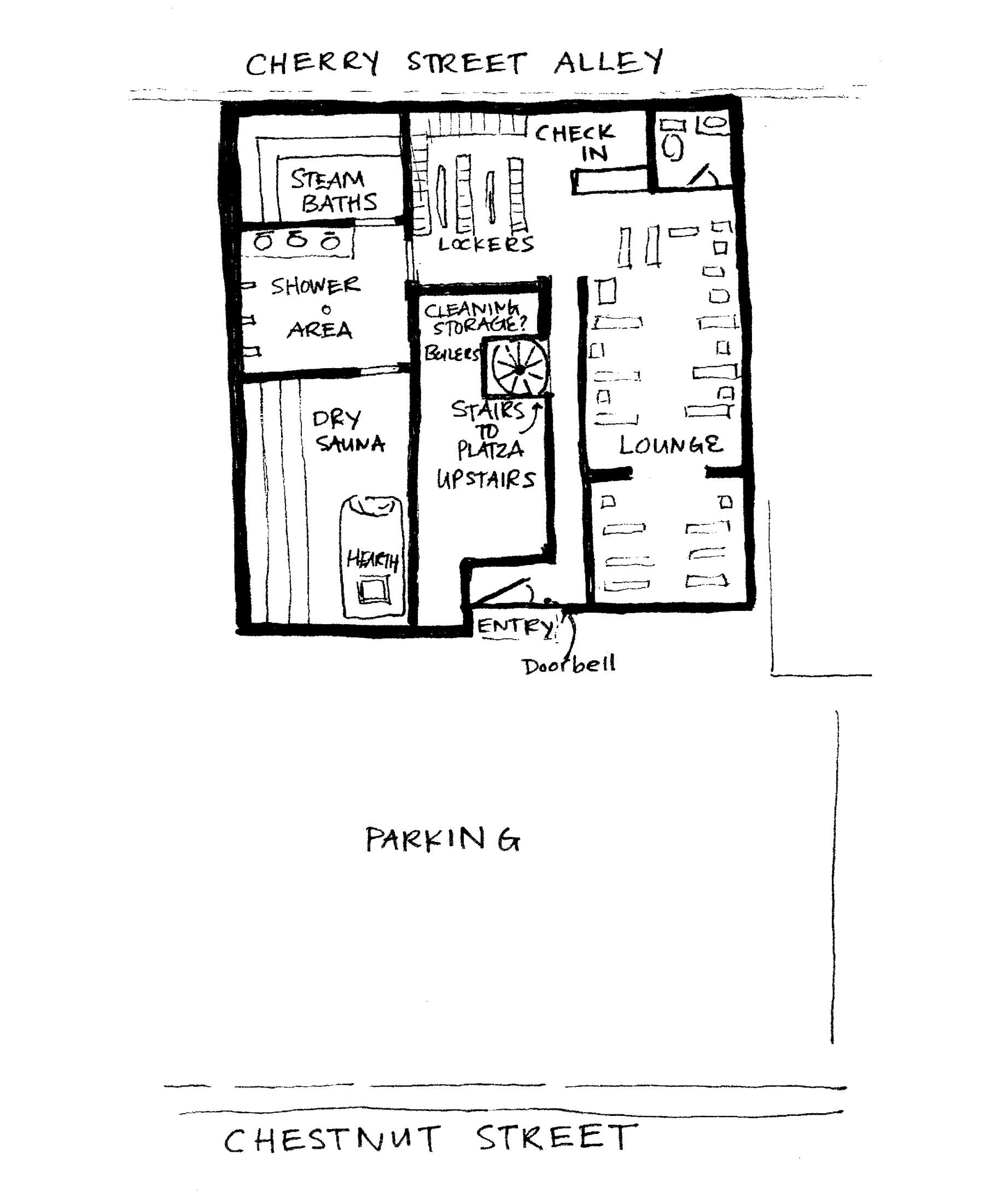

Russians call a sauna or steam experience the shvitz (for sweating) or a banya (for bath, as in one where you get clean through the skin’s osmosis). At Dillons, one can also reserve other traditional services, such as the platza—an oak-branch treatment designed to open the pores for detox and to brush away dead skin cells, a practice some also call “Jewish acupuncture.” To enter Dillons, you ring a buzzer and wait for an attendant to let you in. At the end of the hall, you check in and tuck your belongings away in a locker. To one side, you can enter a shower space that divides the sauna and steam rooms. Regular steamgoers tote a personal shower caddy they’ve packed with their sauna slippers, scrubber gloves, and various toiletries. The other side of the main floor is set up as a lounge, where you can relax in a white leather chair between bouts of shvitzing. If you opt for the platza treatment, that can be found up a tiny spiral staircase leading to the building’s second floor.

Illustration by Alyson Fletcher

For its first 100 years, Dillons operated as a club exclusively for men. A change of ownership in the 1990s opened the door to women one night a week—the solution for mixing things up without seeking costly options for subdividing an already efficient floor plan.

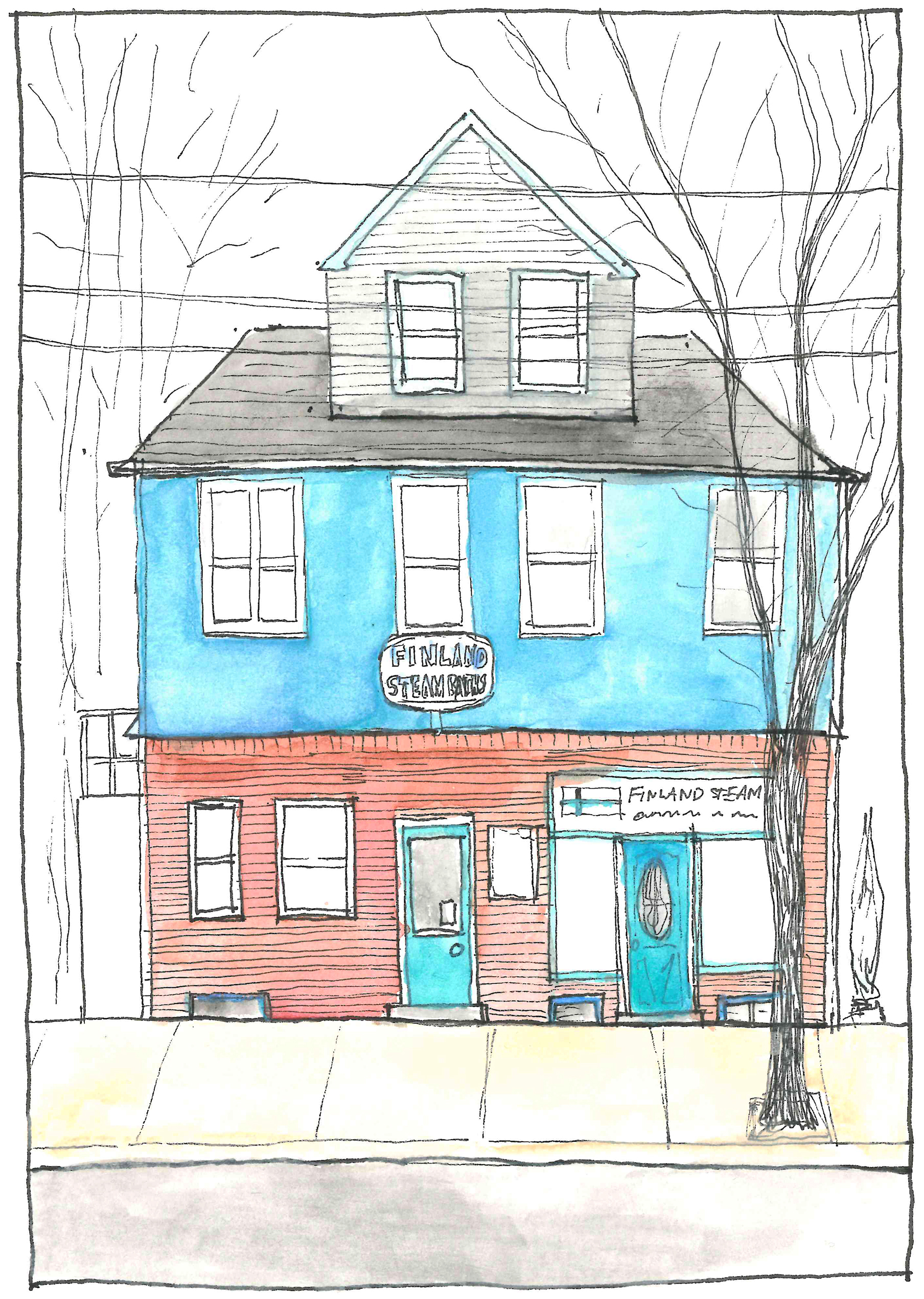

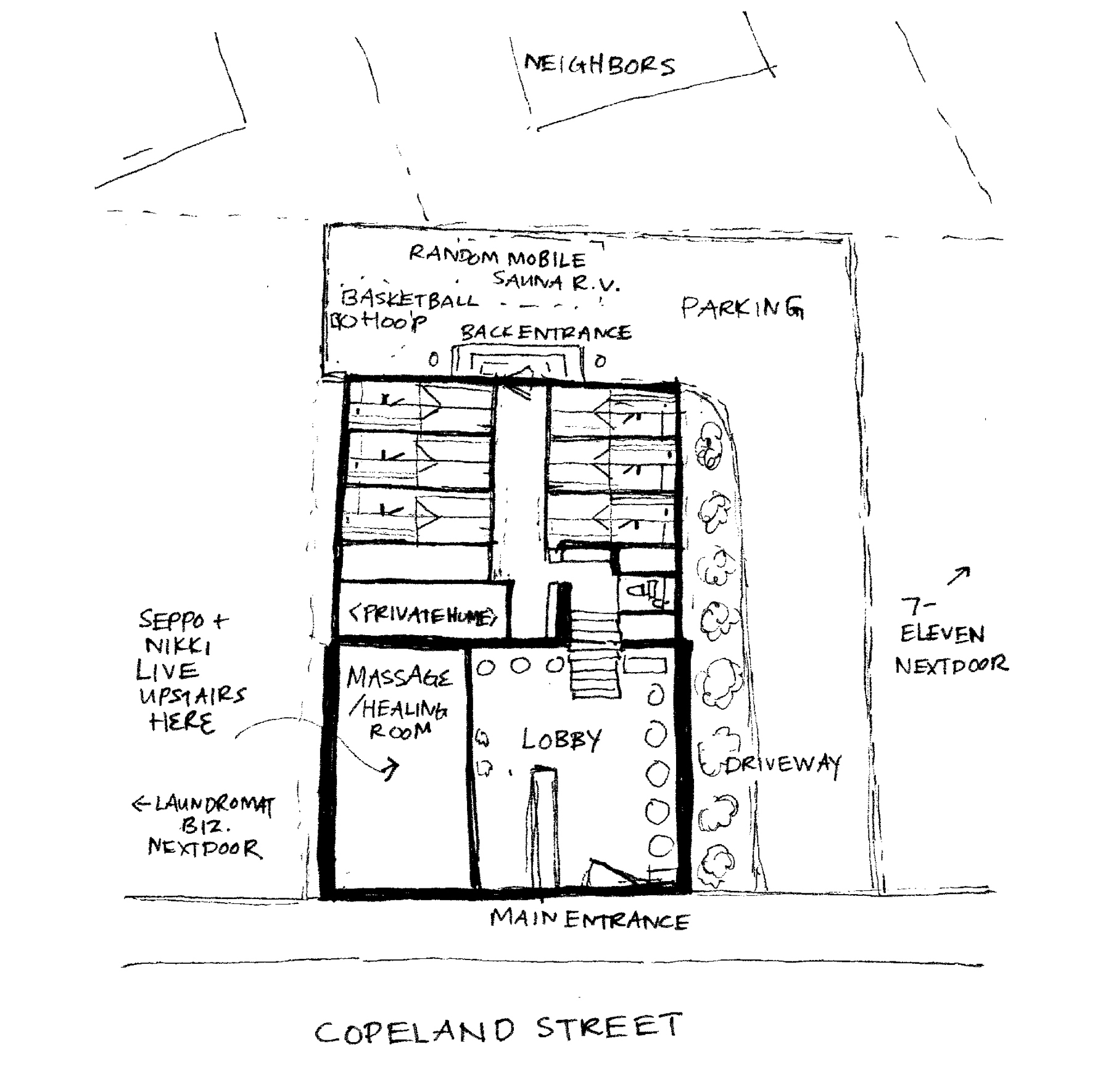

My experience at Dillons took me down a rabbit hole of what else Boston had to offer in this regard, which led me to the Finland Steam Baths, hidden deep in a residential neighborhood of Quincy. You’ll know when you’re there—the building stands out from its neighbors with a façade painted the bright blue of the Finnish flag. Behind the building, six private steam rooms have been glommed on as a house addition. When the original owner built these in 1929, the town had four other immigrant-owned bath businesses like it, to serve Finnish laborers who worked in Quincy’s quarries and shipyard. The other baths have since closed, while this one was passed from a father who bought it in 1969 to his son, Seppo Pakkala, who took over the business in 1990.

Illustration by Alyson Fletcher

Inside the Finland Steam Baths, one signs up for the reservation of a private steam room, available on a first-come, first-served basis. The lobby is filled with healing crystals and comic clippings peppered with sauna humor. Once called up the stairs for your turn, you will pass a mechanical system on the wall filled with metal plates labeled with numbers. This early electrical device keeps track of the time for each room and allows for a buzzer-communication system between the sauna-goer and Pakkala (the sauna master, who also calls himself the “water slosher”). Each private room has four subchambers, divided by walls made of dark-polished fir wood: one in which to change clothes, one in which to steam (where a lever allows you to control the release of steam), one in which to shower in cold water after each steaming bout, and one through which Pakkala accesses the spaces for cleaning while you return to the changing chamber.

Illustration by Alyson Fletcher

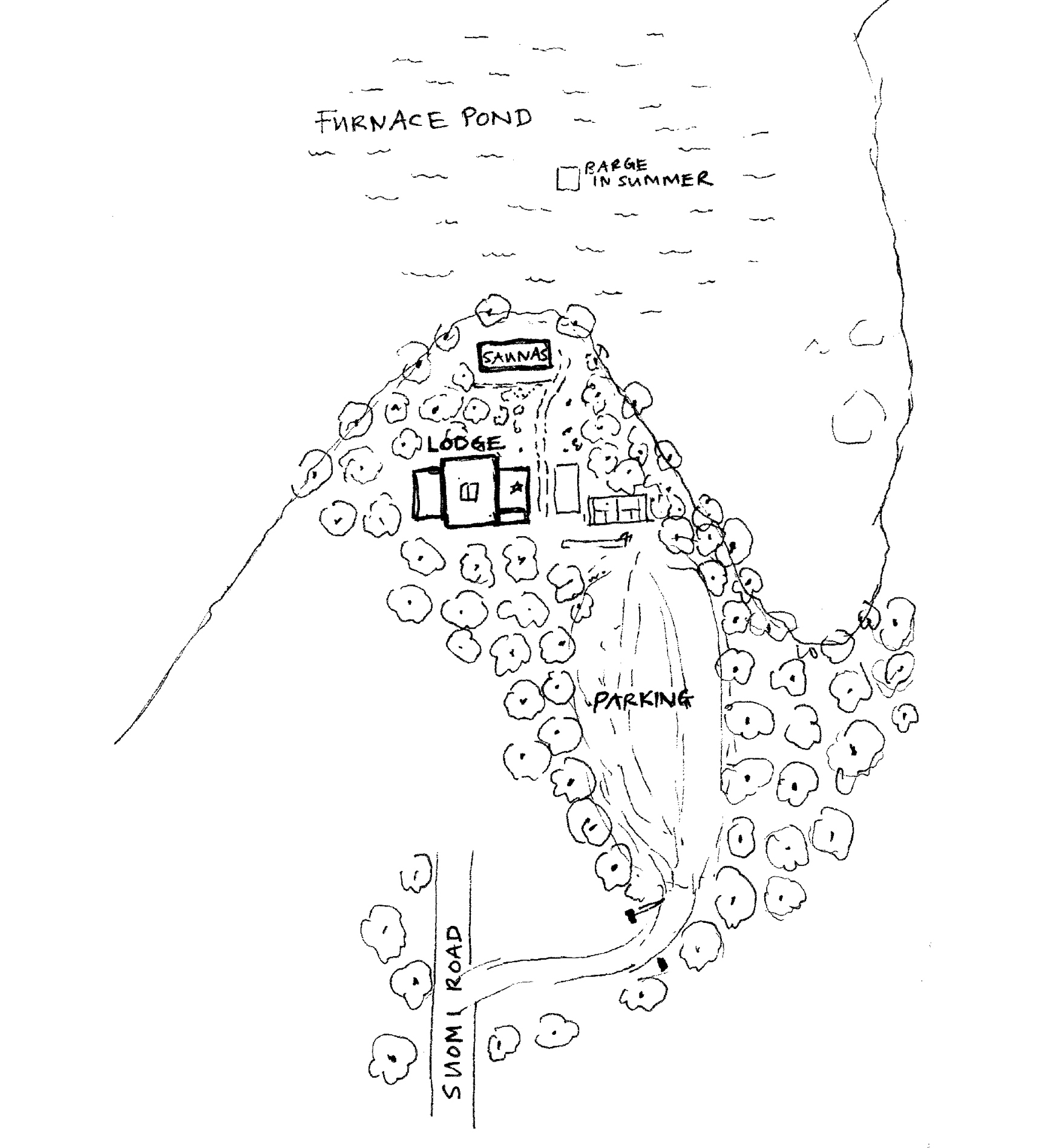

Pakkala told me he is uncertain how much longer he will operate the Finland Steam Baths and, seeing my disappointment, encouraged me to visit the UKTS (Uljas Koitto Temperance Society) camp in Pembroke for the “true wood-fired sauna and frozen-lake experience . . . where all the Finns of Boston go.” UKTS formed in 1896 to use sauna as a ritual to stem drunkenness. It is likely no coincidence that the group found its current sauna home in the 1920s during the height of Prohibition.

The camp is located on Suomi Road, a forested lane that leads to a glacial kettle pond. Suomi means “Finland” in Finnish, fitting given the camp’s landscape looks a lot like that of Finland’s. My first brush with the Finnish sauna experience took place during a summer urban design program in the homeland of architect Alvar Aalto. After our program’s final critique, the professors took us to a camp that looked much like the UKTS camp—set within a pond-dotted forest in central Finland.

In Pembroke, UKTS’s club lodge is made of wood and painted red. The impressive stone hearth within is one clue to the structure’s past life as a hunting lodge. To sign in, you walk through the lodge’s mudroom to a kitchen, where one of the organization’s volunteer members greets you, collects your sauna fee, and explains the order of the camp (how to be a considerate neighbor to those next to you but also how UKTS strives to be a good neighbor as an organization situated within a greater lake community). The society comprises about 50 members who have served as caretakers over the decades, collecting sauna fees, cleaning the buildings, chopping wood from trees downed by storms, and cooking for the crew of volunteers.

Illustration by Alyson Fletcher

The wood-fired sauna house, also made of wood and painted a seafoam green, was built into the hillside adjacent to the lake. A walk down a short path shaded by tall pine trees and lined with piles of artfully arranged chopped wood takes you there. The house has a section for men and one for women, but the genders relax together outside on benches that overlook the pond. In the winter, the club cuts a hole in the ice, where people take dips in the frozen water. In the summer, one can swim to a floating dock and bask under the sun from the middle of the pond.

Both sections have a changing room, a shower room, and a sauna room with varying levels of benches. (The higher you go, the hotter the temperature.) Many who sit at the top are experienced sauna goers and don a sauna hat—made of knit or felted wool that helps shield one’s head from the heat.

The sauna room is full of chatter and laughter, and even strangers strike up conversations about negotiating space on the benches, whether to throw more water on the sauna rocks, how cold the pond is that day, or the general goings-on in one another’s lives. Usually, at least three languages are spoken and may include Russian, Finnish, Belarusian, and Latvian, among others.

Illustration by Alyson Fletcher

Curious as to why so many Nordic immigrants moved to Boston in the first place, I read that some Finns migrated as a result of “Russification,” which aimed to terminate Finnish autonomy. Others were drawn to America’s economic and land opportunities. The Homestead Act of 1862, for example, gave citizens of any background the ability to develop a piece of land, and word traveled fast that America would also pay a good barrel of dollars to skilled laborers. I imagine our climate and geography of kettle ponds could also have made Greater Boston’s landscape feel like a fitting home away from home.

What’s impressive is how the consistent cultural practice of sauna has withstood the test of time in Boston. Many go for the documented physical benefits. Sweating is one of the oldest folk remedies to proactively manage life’s ailments and strengthen the immune system. People have practiced sauna for centuries to detox impurities through the largest organ of the body while also conditioning the heart, relieving sore muscles, and releasing stress. Surrendering to heat can also benefit social bonds, something that’s evident when you visit a sauna with rich cultural and community ties.