Every community has a building that tells its story. The place where things were made, original ideas were sprouted and spread, and individuals discovered their role in the larger whole. These structures dot the American landscape as markers of our collective progress. Their pores are clogged with the community’s sense of self-worth, and their health is a reflection of our own health.

Buildings shouldn’t be preserved in formaldehyde. But discarding the buildings that reveal our nation’s history, with all their patina and rust, isn’t the solution, either. The infrastructure that we have is here to stay, even if the enterprise that once occupied its space is obsolete. The architecture of the future must focus on transformation. It must desurface the potential in our existing built environment with a respect for the past and an eye to the future.

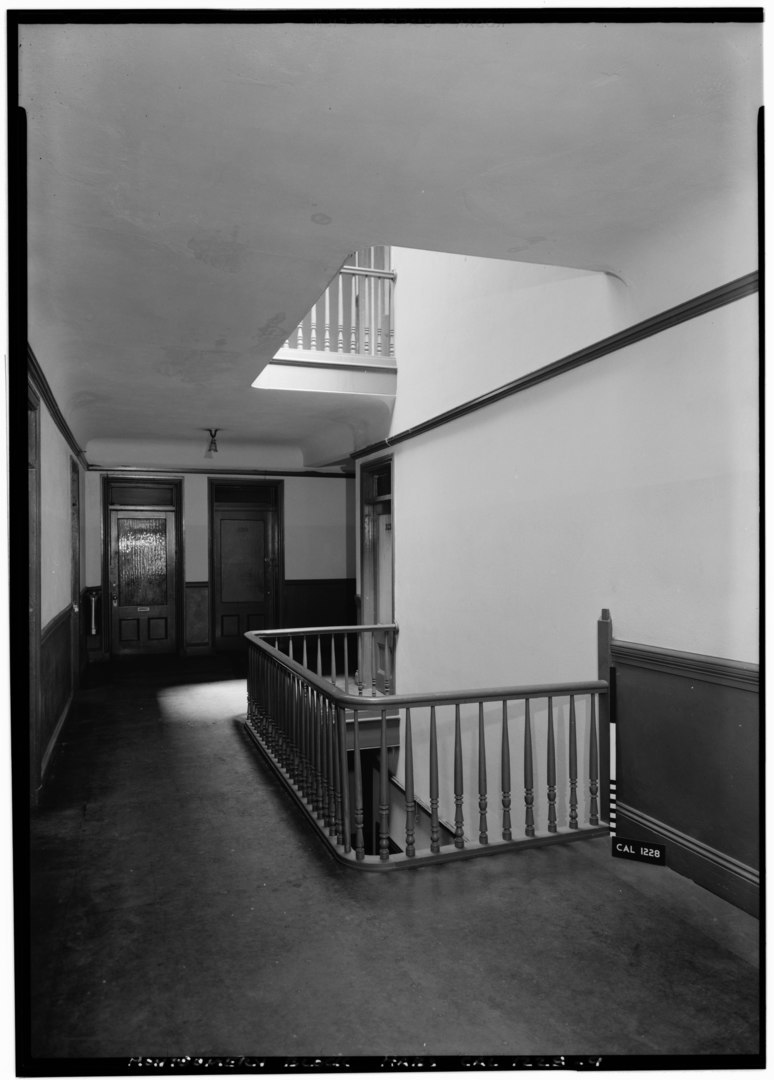

Photo courtesy of Historic American Buildings Survey.

Montgomery Block was the first building in San Francisco’s history designed with fire and earthquakes in mind. It seemed superfluous in 1853 when hundreds of Chinese immigrants dug a crater in the earth for the building’s foundation to rest atop a bed of timbers. But in 1906, its wisdom was revealed, as the Block stood intact and the city around it lay ruined by a massive earthquake.

The Block was a stucco-clad megalith. It had repetitive picture frame windows, an exaggerated cornice, and a courtyard punched into its interior core. Its base was a retail center with three floors of residential units stacked on top. In the early days, the rent was high and attracted professionals. As the city grew and its demographics changed, the suits moved out and artists moved in, converting the units into studios. The confines were cozy and that beget a culture of creative cross-pollination. A scene emerged inside the Block and radiated onto the surrounding neighborhood. At different points in a time frame spanning from the Progressive Era to the New Deal, artists from the likes of Jack London, Ambrose Bierce, Frida Kahlo, and Dorothea Lange lived at Montgomery Block or in the surrounding art district that it spawned.

Montgomery Block was demolished in 1959. The iconic needle in the city’s skyline, the Transamerica Pyramid, pierces through its ghost. As striking and iconic as the Pyramid is, it is surrounded by a cluster of lifeless copycats. It anchors a San Francisco that’s haunted by an inability to maintain affordable housing or a diverse, independent culture that was conjured by its predecessor.

Like Montgomery Block before it, Detroit’s Packard Automotive Plant was cut from the same forward-thinking cloth.

The Packard Plant broke the model of factory construction for the time and, in the process, created a new mold. In the early 1900s, architect Albert Kahn had already designed nine wood structures for the complex, but for the 10th, he employed a system of reinforced concrete that was invented and patented by his brother, Julius. The “Kahn system” angled steel-reinforcement bars at 45 degrees, enabling enormous spans of concrete and allowing for an open floor plan that was infrequently interrupted by the presence of columns. At the building’s perimeter, these long spanning beams were infilled with enormous glass windows that funneled in natural light and cross ventilation. From the roof, glass monitors allowed overhead light to wash the work space.