Is the company town coming back? Well, not in the deliberate way of its forbears, like Pullman, Illinois, or Hershey, Pennsylvania. But the confluence of a booming tech economy, dazzling competition for workers, and overheated housing markets is motivating some companies to consider a 21st-century version.

But the confluence of a booming tech economy, dazzling competition for workers, and overheated housing markets is motivating some companies to consider a 21st-century version.

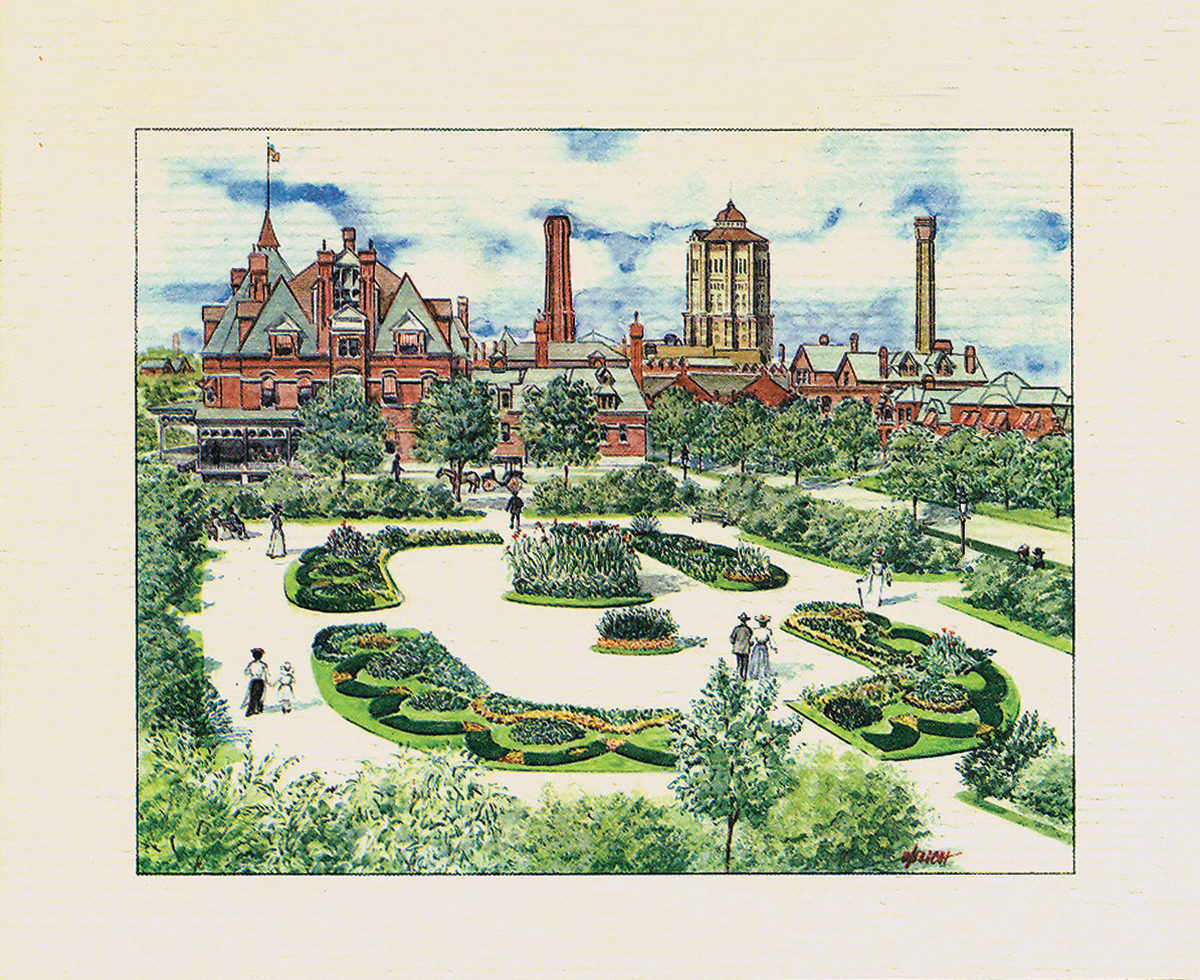

In the age of the industrial revolution, employers had practical reasons for creating company towns. Employers expanded their roles to become more paternalistic, providing not just jobs but housing, healthcare, schools, libraries, churches, and stores. This generosity was less altruistic than strategic: Companies could improve working conditions while deterring workers from activism and unionization. Employees were taken care of but had no autonomy.

Today, the drive for talent, especially in tech centers such as Silicon Valley; Seattle; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Raleigh, North Carolina, has reached a fever pitch. The lengths companies will go to attract the best and brightest are unprecedented. Many new employees have the expectation that their employer will compensate them extremely well but will also operate private transportation shuttles to get them to work; feed them three organic, chef-prepared meals a day; and provide them with onsite services, ranging from haircuts to doggie day care to doctor appointments. Highly competitive recruitment has translated into increasingly jaw-dropping amenities, such as free iPads, lunchtime Pilates, and at-desk massages. The remake of the suburban office park is under way.

It is not surprising then, in hot markets that accompany the healthiest economic ecosystems, that housing might be seen as the ultimate amenity. It certainly is becoming an obstacle, if not the biggest obstacle, to hiring in these locations. But is it enough of one for employers to embrace the company town anew?

Sort of.

Call it the company town disrupted: The trend on the horizon isn’t a paternalistic employer exploiting the trust and desperation of low-wage workers. To the contrary, Company Town 2.0 is a walkable, amenity-rich offering for highly paid knowledge workers that has emerged as an indispensable tool for hiring the better engineer. As Jim Morgensen, vice president of Global Workplace Services for LinkedIn, based in Mountain View, California, explains, “Housing affordability has become a critical issue companies are facing in the Bay Area in terms of their ability to attract and retain talent, and as an employer, we need to support the creation of additional housing near jobs and transit.”

These “new towns” are more New Urbanist than Manhattan-ish. Dense cities chock-full of tech clusters lack the square footage to accommodate the giant floor plates so many companies seek, for one. (Frank Gehry’s single-story, open-plan Facebook building holds 2,800 employees in 430,000 square feet, for example.) And many feel that verticality (as in high-rise) deters the “spontaneous cultural collisions” believed to be so integral to the narrative of innovation.

Wired referred to Menlo Park as “Facebookville, California. Population: 38,207” in a 2015 article about the company’s plan to begin to build housing for some of its employees. Although 394 units of housing does not a company town make, when companies like this one occupy such a large literal and psychic footprint in a city, one might argue that yes, a new paradigm has emerged. (And there’s Apple, which occupies 60 percent of land in Cupertino, has offices in Sunnyvale, and will soon add 16,000 jobs to San Jose; and Google, which occupies so much real estate in Mountain View that it can feel very much like a company town, even without any worker housing.)

Earlier this year, the town of Burlington, Massachusetts, approved the Center at Corporate Drive, a 480,000-square-foot Class A office park on 47 acres. Complementing the four-building park will be abundant amenities (including child-care facilities, fitness centers, a plethora of restaurants and, oddly, five Dunkin’ Donuts) and 271 residences that “will allow young professionals an option to live in a new state-of-the-art apartment complex and to be in close proximity to the top-notch employment options located in town,” said Robert Buckley, the project attorney. The residences will be attractive and ideal for seniors and young professionals alike, he explained, due to their close proximity to a rich mix of dining and entertainment options.

Workers aged 25-34 are staying in jobs for an average of just three years. And more young adults aged 18 to 34 are living at home with their parents than a spouse or partner.

In Raleigh, Research Triangle Park (RTP) recognized that millennials were loath to situate themselves within its traditional corporate surroundings. The Park offered a convenient commute, but its owners saw that almost 40,000 people traveled to it every day — and then left to spend their money elsewhere.